What is Yersinia pestis?

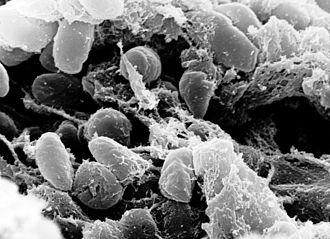

Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic bacterium, is the causative agent of plague, a historically devastating disease responsible for countless deaths. Its unique characteristics, environmental adaptability, and potent virulence factors contribute to its dangerous nature, making it a significant public health concern.

Table of Contents

Characteristics

The characteristics of Yersinia pestis,

Morphology

Y. pestis is a rod-shaped bacterium, typically measuring 0.5-1.0µm in width and 1.0-3.0µm in length. It exhibits a characteristic bipolar staining pattern, appearing as a “safety pin” due to the presence of metachromatic granules at its poles.

Culture

Y. pestis grows optimally at 28°C, but can also thrive at temperatures ranging from 4°C to 40°C. It is readily cultured on standard media like blood agar, forming small, white colonies with a characteristic “fried egg” appearance.

Genetics

Y. pestis is genetically closely related to other Yersinia species like Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica. Its genome contains a unique “plasmid-borne virulence factor” (pYV) crucial for its pathogenic potential.

Habitat and Transmission

The Habitat and Transmission of Yersinia pestis,

Reservoir

Y. pestis primarily resides in wild rodents, particularly black rats (Rattus rattus), which act as its natural reservoir.

Transmission

Plague transmission occurs through the bite of infected fleas, primarily the Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis). Fleas acquire Y. pestis by feeding on infected rodents, becoming infected themselves. When the infected flea bites a human or other susceptible animal, Y. pestis is injected into the bloodstream.

Other routes

Plague can also be transmitted through direct contact with infected animals or humans, including handling infected carcasses or exposure to bodily fluids. Airborne transmission, though rare, can occur in cases of pneumonic plague, where the bacteria infect the lungs.

Virulence Factors

Yersinia pestis possesses a remarkable arsenal of virulence factors that contribute to its deadly nature. These factors allow it to evade host defenses, proliferate, and cause systemic disease:

Yersinia outer membrane protein (Yop)

This group of proteins secreted by Y. pestis plays a crucial role in suppressing the host immune system. Yops disrupt phagocytosis, inhibit cytokine production, and interfere with cell signaling pathways.

YopE

Inhibits Rho GTPases, crucial for actin polymerization and cell signaling, leading to cell death and decreased inflammation.

YopH

De-phosphorylates tyrosine kinases, hindering immune cell activation and signaling.

YopJ

Blocks NF-κB activation, a key transcription factor for pro-inflammatory cytokine production.

Pla

A plasminogen activator encoded by Y. pestis, Pla converts plasminogen into plasmin, an enzyme that breaks down fibrin clots. This allows the bacteria to spread throughout the bloodstream and reach target organs.

F1 antigen

A capsule-like structure surrounding Yersinia pestis, this antigen aids in resisting phagocytosis by macrophages, a critical immune defense mechanism.

LPS

Lipopolysaccharide, a component of the outer membrane, is an endotoxin that triggers the release of inflammatory mediators, contributing to the severe symptoms of plague.

Clinical Manifestations of Plague

Depending on the route of infection and the host’s immune status, Yersinia pestis can cause different forms of plague:

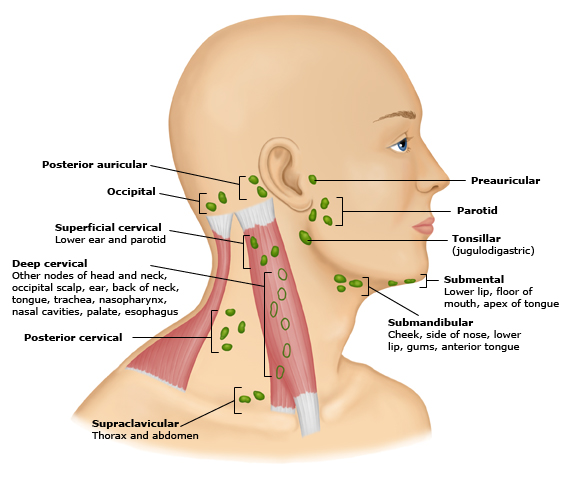

Bubonic plague

The most common form of plague, characterized by painful, swollen lymph nodes (buboes) typically in the groin, armpit, or neck. It results from the bacteria being injected into the bloodstream through a flea bite.

Septicemic plague

This form occurs when the bacteria multiply rapidly in the bloodstream, leading to septic shock, organ failure, and potentially death.

Pneumonic plague

This highly contagious form of plague develops when the bacteria reach the lungs. It is characterized by fever, cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain. Pneumonic plague can be fatal within 24 hours if left untreated.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosis of plague typically involves laboratory confirmation through culture, serological tests, or PCR (polymerase chain reaction) techniques. Prompt treatment with antibiotics, such as gentamicin or streptomycin, is essential for survival. However, the effectiveness of antibiotics decreases with the progression of disease.

Prevention

Preventing plague transmission involves measures like:

Rodent control

Reducing rodent populations through sanitation and pest control methods.

Flea control

Using insecticides to eliminate fleas from homes and areas where rodents are prevalent.

Vaccination

A vaccine for plague is available but is not widely used, primarily recommended for individuals at high risk of exposure, such as laboratory workers.

Personal protection

Avoiding contact with rodents and their fleas, using appropriate protective clothing during travel to endemic areas, and seeking medical attention promptly if symptoms suggestive of plague occur.

Conclusion

Yersinia pestis remains a potent threat to human health, underscoring the importance of understanding its characteristics, habitat, and virulence factors. Public health measures, including effective surveillance, rapid diagnosis, timely treatment, and targeted prevention strategies, are essential in mitigating the risk of plague outbreaks and ensuring the safety of human populations.

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ)

What is Pneumonic plague?

Yersinia pestis is the bacterium that causes the extremely contagious and fatal lung sickness known as pneumonic plague. Unlike bubonic plague, which mainly affects the lymph nodes, this type of plague is not contagious.

What is Rho GTPases?

A family of tiny, widely distributed proteins known as Rho GTPases functions as a molecular switch, essential for controlling a number of different cellular functions. Their function in cell motility, cytoskeletal dynamics, and cell signaling is well recognized.

Related Articles