Define Virus Replication?

Virus replication is the process through which a virus makes copies of itself after infecting a host cell. Viruses are tiny organisms that are much smaller than bacteria, and unlike bacteria, they cannot live or multiply on their own. Viruses need to invade a living host cell to survive and replicate.

This process is what leads to infections and, in many cases, diseases. Understanding how viruses replicate inside our bodies can give us a better grasp of how infections spread and why our immune system reacts the way it does.

Table of Contents

Imagine viruses as extremely cunning intruders, whose only goal is to multiply and spread. They don’t have their own tools to do this, so they hijack the host cell’s machinery to make copies of themselves. In simple terms, the virus tricks our cells into becoming virus factories. The process involves a series of steps, each crucial to the virus’s ability to survive and spread. Let’s walk through the virus replication cycle step by step, using common viruses like the flu or cold virus as examples.

Steps of Virus Replication

The steps in Virus Replication ,

Step 1: Attachment (Entering the Host Cell)

The first step in virus replication is attachment. Think of this step like a thief trying to break into a house. The virus needs to find the right “key” to unlock the door to the host cell. The “key” is a special protein on the surface of the virus, and the “door” is a receptor on the surface of the host cell. Different types of viruses have specific keys that fit only certain doors, which is why some viruses infect certain types of cells. For example, the flu virus targets cells in the respiratory tract, while the HIV virus targets immune cells.

Once the virus finds the right receptor, it attaches itself firmly to the cell, like a magnet sticking to a refrigerator. This attachment is the critical first step, without which the virus cannot enter the cell or start replicating.

Example: In the case of the flu, the influenza virus uses a protein called hemagglutinin (its key) to bind to receptors on the surface of the respiratory cells in your throat and lungs. This is why you often feel congestion, coughing, or sore throat when you catch the flu.

Step 2: Penetration (Getting Inside the Cell)

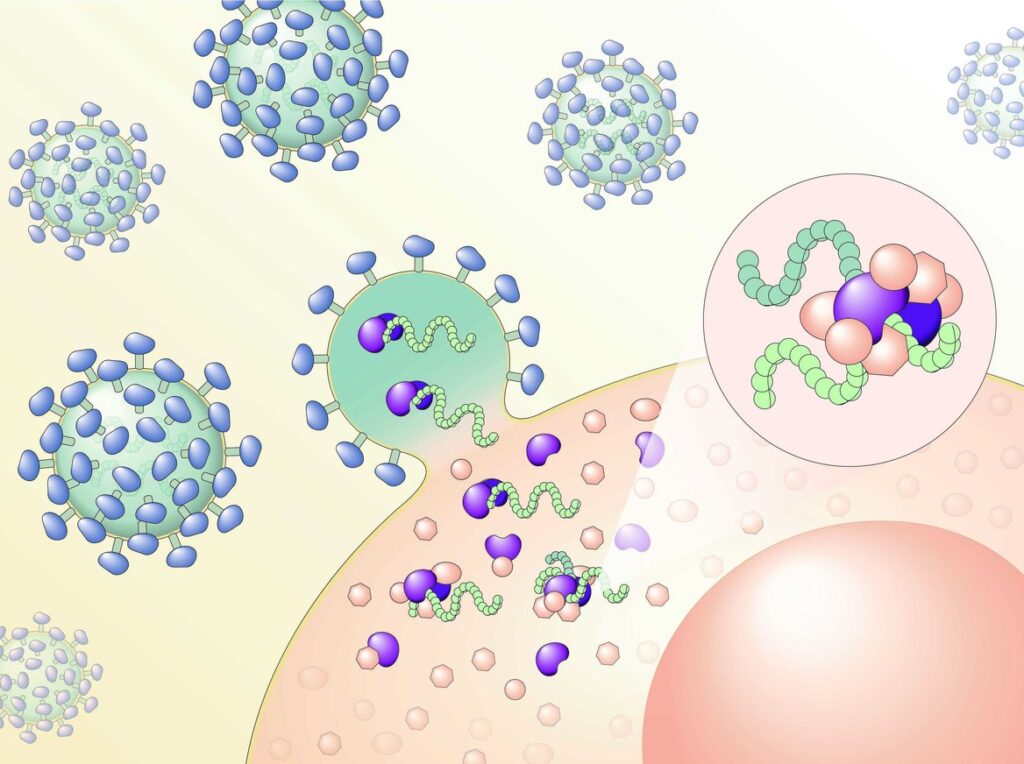

Once attached, the virus now has to get inside the cell, which is known as penetration. This can happen in two main ways. Either the virus injects its genetic material (DNA or RNA) into the cell, leaving the outer shell outside, or the entire virus enters the cell through a process called endocytosis. In this case, the host cell actually engulfs the virus, like swallowing a tiny particle.

Think of this step like a thief getting inside the house and looking for the valuable items inside. The “valuable item” here is the virus’s genetic material, which carries all the instructions for making new viruses.

Example: The HIV virus enters immune cells by fusing with the cell membrane and releasing its RNA into the cell. On the other hand, viruses like the herpes virus get swallowed up by the cell and then release their DNA inside.

Step 3: Uncoating (Revealing the Blueprint)

Once inside the cell, the virus has to reveal its genetic blueprint so that it can start taking over the cell’s machinery. This step is called uncoating. The virus sheds its outer coat, much like taking off a jacket when you enter a house, exposing the viral DNA or RNA inside.

This genetic material is what the virus needs to use in order to hijack the cell. The host cell, now fooled, starts reading the viral genetic material as if it were its own, thinking that it needs to follow the instructions given by the virus.

Example: Once inside a respiratory cell, the flu virus uncoats and releases its RNA, which carries the instructions for making new flu viruses. The cell then starts reading these instructions, unaware that it is helping the virus replicate.

Step 4: Replication (Making Copies of the Virus)

With the viral genetic material now exposed inside the host cell, the cell starts following the instructions to make new viral components. This includes copying the viral RNA or DNA and producing the proteins that will make up the new viruses. The cell’s machinery is essentially turned into a virus-making factory.

This is the stage where the virus makes copies of itself. Just as a factory might produce hundreds or thousands of identical products, the infected cell churns out viral components to be assembled later into complete viruses. The virus doesn’t do any of this on its own; it relies entirely on the host cell to produce everything it needs.

Example: In a cold virus infection, the infected cells in your throat and nose begin replicating the viral RNA and producing viral proteins. Soon, these cells are filled with pieces of the cold virus that are just waiting to be assembled.

Step 5: Assembly (Putting the Virus Together)

After all the viral components have been produced, they need to be assembled into complete viruses. Think of this as a final step in a production line, where all the parts of the virus – the genetic material, the proteins, and the outer shell – come together to form new, functional viruses.

Once assembled, the viruses are ready to leave the cell and infect new cells. It’s like the factory now has hundreds or thousands of new thieves, all ready to break into other houses and repeat the process.

Example: Inside the cells of someone with the flu, viral RNA, proteins, and envelopes are put together to form thousands of new flu viruses, ready to burst out of the cell and spread to other parts of the respiratory tract.

Step 6: Release (Exiting the Cell)

The final step in virus replication is the release of new viruses from the host cell. This can happen in two main ways: either the viruses cause the cell to burst open (a process called lysis), killing the cell in the process, or the viruses can “bud” off from the cell, taking part of the cell membrane with them, but leaving the cell alive to keep making more viruses.

Once released, the new viruses are free to infect other cells in the body, continuing the cycle of infection. In many cases, this rapid spread of viruses throughout the body is what causes the symptoms of a viral infection, such as fever, coughing, or a sore throat.

Example: In the case of COVID-19, the virus infects lung cells, which then burst and release thousands of new viruses. These viruses go on to infect more lung cells, which can lead to severe respiratory symptoms as more and more cells are destroyed.

Outcomes of Virus Replication

Infection and Spread

Once viruses start replicating, they spread throughout the body, infecting more and more cells. For example, when you catch a cold, the virus spreads from one cell in your nose or throat to thousands of others, causing congestion, runny nose, and coughing.

Damage to Cells

As viruses burst out of cells or hijack their machinery, they often kill or damage the cells. This is why viral infections can lead to symptoms like sore throat, organ damage, or even death in severe cases. For instance, in COVID-19, lung cells are destroyed, leading to difficulty breathing and pneumonia in severe cases.

Immune System Activation

Your body’s immune system recognizes the presence of the virus and starts fighting back. This immune response causes inflammation, fever, and other symptoms of illness. While these symptoms are uncomfortable, they are part of the body’s defense system trying to eliminate the virus.

Possible Recovery or Chronic Infection

In many cases, the immune system eventually clears out the virus, leading to recovery. For example, most people recover from the flu in a week or two as their immune system destroys the virus. However, in some cases, like HIV or herpes, the virus remains in the body and continues to replicate over time, leading to chronic infection.

Conclusion

Virus replication is a fascinating but dangerous process. By hijacking the host cell’s machinery, viruses can create thousands of copies of themselves, leading to widespread infection and illness. Understanding this process is crucial for developing vaccines and treatments that can stop viruses in their tracks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Virus replication?

Virus replication is the process through which a virus makes copies of itself after infecting a host cell. Viruses are tiny organisms that are much smaller than bacteria, and unlike bacteria, they cannot live or multiply on their own.

What do you meab by hemagglutinin?

Hemagglutinin, any of a group of naturally occurring glycoproteins that cause red blood cells (erythrocytes) to agglutinate, or clump together. These substances are found in plants, invertebrates, and certain microorganisms.

Write the Outcomes of Virus Replication?

The outcome of Virus Replication are,

Infection and spread, Damage to cells, Immune System Activation, Possible Recovery or Chronic Infection

Related Articles