Introduction

Rotavirus remains a critical public health concern, particularly for pediatric populations, contributing significantly to the global diarrheal disease burden. This survey note aims to provide a comprehensive, textbook-style exploration of rotavirus, covering its classification, structure, composition, properties, replication, mode of transmission, pathogenesis, clinical symptoms, laboratory diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control, as of June 2025. The information is synthesized from authoritative sources to ensure accuracy and depth, suitable for academic and professional use.

Summary of Rotavirus

- Rotavirus is a small, wheel-shaped virus with 11 segments of double-stranded RNA that mainly infects young children.

- It attacks the cells lining the small intestine, leading to severe diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration.

- The virus spreads through contaminated food, water, or contact, and can be prevented through good hygiene and vaccination.

Table of Contents

Classification of Rotavirus

It is classified within the Reoviridae family, a group of non-enveloped, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) viruses, under the genus Rotavirus. The taxonomic hierarchy includes:

Family: Reoviridae

Genus: Rotavirus

Species: Rotavirus A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, and others, with humans primarily affected by species A, B, and C, and A causing over 90% of infections.

Serogroups are defined by the antigenic properties of the VP6 protein, with groups A-J identified. Within Rotavirus A, serotypes are further classified based on two outer capsid proteins:

- G-type (VP7, glycoprotein): Determines serotype specificity.

- P-type (VP4, protease-sensitive): Adds to antigenic diversity.

Common serotypes include G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], G4P[8], and G9P[8], with over 70 G-P combinations noted, reflecting significant genetic diversity.

Structure, Composition, and Properties of Rotavirus

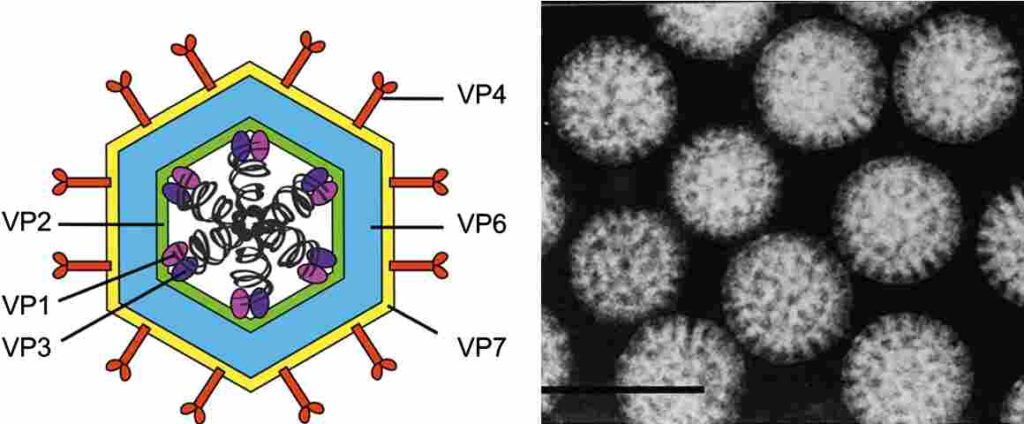

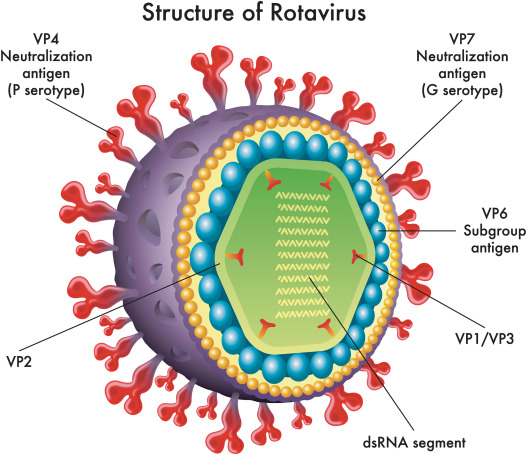

Rotavirus exhibits a distinctive wheel-like appearance under electron microscopy, justifying its name from the Latin rota (“wheel”). It is non-enveloped, with an icosahedral, triple-layered capsid, approximately 70–100 nm in diameter.

Structure

- Capsid Layers:

- Outer capsid: Composed of VP7 (glycoprotein) and VP4 (protease-sensitive, forming spikes), cleaved by host proteases like trypsin into VP5* and VP8* for enhanced infectivity.

- Inner capsid: Formed by VP6, defining group-specific antigens.

- Core: Encases the genome, with VP2 as the primary structural protein, VP1 (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase), and VP3 (capping enzyme).

Genome and Composition of Rotavirus

- The genome comprises 11 segments of dsRNA, totaling 18,555 nucleotides, encoding six structural proteins (VP1–VP4, VP6, VP7) and six non-structural proteins (NSP1–NSP6, with segment 11 potentially encoding two).

- Proteins include structural (core, inner, outer capsid) and non-structural (e.g., NSP4 as enterotoxin, NSP1 as interferon antagonist).

- The virus lacks lipids as it is non-enveloped.

- VP7 is glycosylated, contributing to antigenicity.

Properties of Rotavirus

Rotavirus is environmentally stable, surviving on surfaces for 9–19 days and resistant to many disinfectants, but is inactivated by heat (60°C for 30 minutes), ethanol, and chlorine. It primarily infects mammals and birds, with Rotavirus A most significant in humans. It shows antigenic variation due to genetic reassortment and mutations, complicating vaccine strategies.

Replication of Rotavirus

Replication occurs in the cytoplasm of mature enterocytes in the small intestine, with a rapid cycle (12–18 hours):

- Attachment and Entry: VP8* (VP4 subunit) binds to receptors like sialic acid or histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs), with VP7 aiding; entry occurs via endocytosis or membrane penetration.

- Uncoating: Low pH in endosomes triggers outer capsid loss, forming double-layered particles (DLPs).

- Transcription: DLP transcribes dsRNA into positive-sense ssRNA using VP1 (polymerase), within viroplasms formed by NSP2 and NSP5.

- Translation: Host ribosomes translate mRNA, with NSP3 enhancing viral translation by inhibiting host synthesis.

- Genome Replication: Positive-sense RNA templates negative-sense RNA, forming new dsRNA in viroplasms.

- Assembly: Core (VP2, VP1, VP3) encapsidates genome, VP6 forms DLPs, budding into the ER with VP7 and VP4 forming triple-layered particles (TLPs), facilitated by NSP4.

- Release: Via cell lysis or exocytosis, causing enterocyte death.

This process disrupts gut function, contributing to diarrhea.

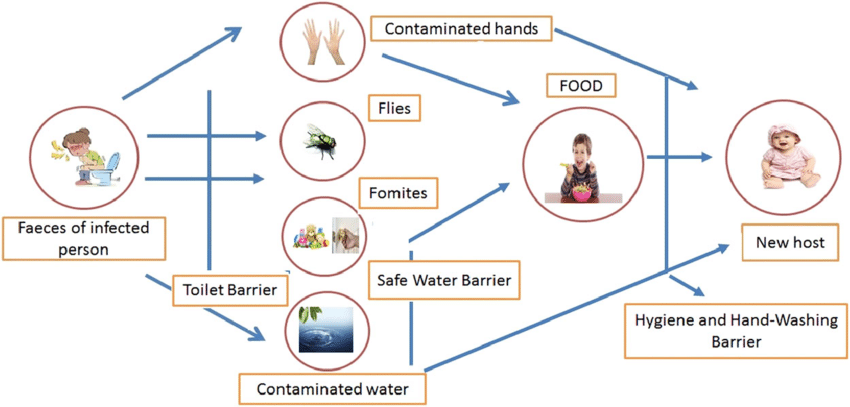

Mode of Transmission of Rotavirus

Rotavirus spreads primarily via the fecal-oral route and is highly contagious:

- Direct Contact: Person-to-person via contaminated hands or surfaces.

- Contaminated Food/Water: Ingestion of infected materials.

- Fomites: Contact with contaminated objects (e.g., toys, utensils), common in daycare settings.

- Aerosol Transmission: Rare, possibly via respiratory droplets.

High viral shedding (up to 10^12 particles/gram feces), environmental stability, and low infectious dose (<100 particles) contribute to spread. It peaks in winter/spring in temperate climates and occurs year-round in the tropics.

Pathogenesis of Rotavirus

Rotavirus infects mature enterocytes, causing diarrheal disease:

- Enterocyte Destruction: Replication causes cell lysis, reducing absorptive surface and causing malabsorption diarrhea.

- Enterotoxin Activity: NSP4 disrupts tight junctions, increases calcium, activates chloride secretion, causing secretory diarrhea.

- Enteric Nervous System: NSP4 and viral replication stimulate motility and fluid secretion, worsening symptoms.

- Immune Response: Cytokine release contributes to inflammation and tissue damage.

The disease has a 1–3 day incubation, villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, peaking at 3–7 days, with viral shedding up to 10 days, longer in immunocompromised patients.

Clinical Symptoms of Rotavirus

Rotavirus causes acute gastroenteritis, characterized by:

- Watery diarrhea, vomiting (often severe initially), and low to moderate fever.

- Duration of illness ranges from 3 to 8 days, with severe cases risking dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and metabolic acidosis.

- Complications like seizures and encephalopathy are rare but more common in immunocompromised individuals.

- High-risk groups include children under 5 years, especially 6 months to 2 years, immunocompromised patients, and elderly adults during outbreaks.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Rotavirus

Diagnosis helps distinguish rotavirus from other causes of gastroenteritis:

- Antigen Detection: Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) targeting VP6 is highly sensitive. Latex agglutination tests provide rapid but less sensitive results.

- Molecular Methods: RT-PCR and real-time PCR detect viral RNA and allow serotyping; these are more advanced but increasingly common.

- Electron Microscopy: Visualizes characteristic wheel-shaped particles but is expensive and rarely used.

- Serology: IgM and IgG detection used mainly for epidemiological studies, not routine diagnosis.

Stool samples collected during the acute phase (3–5 days after symptom onset) are preferred.

Treatment of Rotavirus

There is no specific antiviral treatment for rotavirus infection. Care focuses on supportive management:

- Rehydration: Oral rehydration solution (ORS) containing glucose, sodium, and potassium is the mainstay. Intravenous fluids are needed in severe dehydration.

- Nutritional Support: Early refeeding with breast milk or formula is recommended; lactose-free formulas may be used if lactose intolerance develops.

- Adjunctive Therapies: Zinc supplementation can reduce disease duration and severity. Probiotics may provide some benefit. Antidiarrheal medications like loperamide are avoided, and antibiotics are not indicated unless bacterial co-infection is confirmed.

Prevention and Control of Rotavirus

Preventing rotavirus infection requires combined efforts:

- Vaccination: Two main vaccines are available: Rotarix (2 doses at 2 and 4 months) and RotaTeq (3 doses at 2, 4, and 6 months). Vaccination is 85–98% effective in high-income countries and 50–70% in low-income settings. New vaccines are expanding access globally.

- Hygiene: Regular handwashing, safe food and water, and thorough surface disinfection using chlorine-containing agents reduce spread.

- Public Health Measures: Surveillance, health education, infection control practices (isolation, proper disposal of contaminated materials), and promoting breastfeeding for passive immunity are essential.

Epidemiology and Global Impact

Before vaccines, rotavirus caused about 500,000 deaths annually in children under 5, predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Vaccination programs have reduced deaths to around 200,000 per year. The virus shows seasonal peaks in temperate regions during winter and spring, with year-round activity in tropical areas.

Challenges and Future Directions

Challenges include lower vaccine efficacy in low-income countries due to malnutrition and co-infections, antigenic diversity of strains, and issues with vaccine access and cost. Future directions focus on developing parenteral vaccines, antiviral therapies, and global health initiatives to improve coverage and sanitation.

Conclusion

Rotavirus continues to pose a significant health threat, especially to young children worldwide. However, vaccination and improved hygiene have markedly reduced its impact. Continued research and public health efforts are vital to close remaining gaps in vaccine efficacy and access, working toward global health equity and the reduction of rotavirus-related illness and death.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is There a Rotavirus Vaccine?

Yes, there are two main vaccines: Rotarix and RotaTeq. These vaccines are safe and effective in preventing severe rotavirus infections and are included in the immunization schedules of many countries.

How Can Rotavirus Infection Be Prevented?

The most effective prevention method is vaccination. The rotavirus vaccine is administered orally in two or three doses, starting at 2 months of age. Additionally, practicing good hygiene, such as frequent handwashing and disinfecting surfaces, can help reduce transmission.

What Are the Symptoms of Rotavirus Infection?

Symptoms include sudden onset of watery diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain. Dehydration is a significant concern, especially in young children, and can lead to hospitalization if not managed promptly.

Related Articles