Entamoeba histolytica is a protozoan parasite that infects humans and is responsible for a range of intestinal and extraintestinal diseases collectively referred to as amoebiasis. The parasite primarily colonizes the large intestine, where it may exist as a harmless commensal or cause tissue invasion resulting in disease. Globally, amoebiasis is a significant public health issue, especially in areas with inadequate sanitation and limited access to clean water. The disease affects both sexes and all age groups, though it is more common in adults and immunocompromised individuals. Due to its medical importance and potential for severe complications, understanding the biology and clinical features of Entamoeba histolytica is essential for healthcare professionals, microbiologists, and epidemiologists.

Summary of Entamoeba histolytica

- Entamoeba histolytica is a protozoan parasite that causes amoebiasis, commonly transmitted through contaminated food and water in areas with poor sanitation.

- It exists in three forms: trophozoite (invasive), precyst (transitional), and cyst (infective), with the cyst form responsible for disease transmission.

- Clinical manifestations range from asymptomatic infection to severe dysentery and liver abscess, diagnosed by microscopy, serology, and molecular tests, and treated with anti-amoebic drugs like Metronidazole and luminal agents.

Table of Contents

Morphology of Entamoeba histolytica

Entamoeba histolytica occurs in three distinct morphological forms, each performing a specific function in its life cycle and contributing to its pathogenicity. These forms are the trophozoite, the precystic form, and the cyst. Morphological identification plays a vital role in differentiating Entamoeba histolytica from other non-pathogenic amoebae.

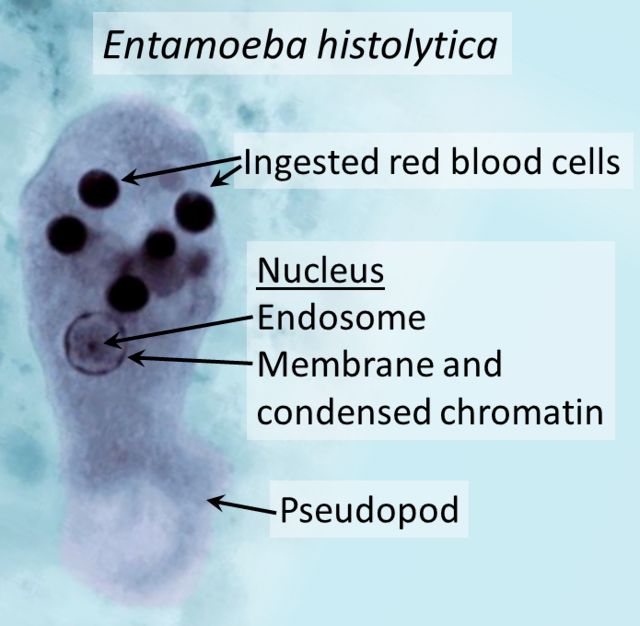

Trophozoite

The trophozoite represents the actively feeding, motile, and pathogenic stage of Entamoeba histolytica. Measuring approximately 15 to 30 micrometers in diameter, it moves using pseudopodia, which are temporary cytoplasmic projections. The cytoplasm is differentiated into a clear ectoplasm and a granular endoplasm containing ingested food particles, bacteria, and frequently, red blood cells. The spherical nucleus has a central karyosome and a delicate nuclear membrane lined with fine granules of peripheral chromatin. A diagnostic feature of pathogenic trophozoites is the presence of ingested erythrocytes, which indicates active tissue invasion. This form is fragile and does not survive long outside the host.

Precystic Form

The precystic form is a transitional, non-motile stage between the trophozoite and the cyst. It is smaller than the trophozoite, typically measuring 10 to 20 micrometers, and is round or ovoid in shape. The precystic form prepares for encystation by expelling food vacuoles and retracting its pseudopodia, resulting in a clear and homogenous cytoplasm. The nucleus resembles that of the trophozoite, maintaining a central karyosome. Though rarely encountered in routine stool examinations, it plays a crucial role in the life cycle as it transforms into the infective cyst. This form is more resilient than the trophozoite but still susceptible to environmental changes.

Cyst

The cyst is the infective, environmentally resistant stage of Entamoeba histolytica responsible for transmission. Mature cysts are spherical and measure approximately 10 to 15 micrometers in diameter, surrounded by a tough, refractile wall that enables them to withstand desiccation and chlorination. Initially, immature cysts contain a single nucleus, but nuclear division occurs to form two, then four nuclei in mature cysts. Chromatoid bodies, rod-shaped structures with rounded ends, are often present in immature cysts but typically disappear in mature forms. These structures play a role in the encystation process. The cyst’s resilience allows it to survive for weeks in moist environments, making it a potent agent of transmission in areas lacking adequate sanitation.

Life Cycle of Entamoeba histolytica

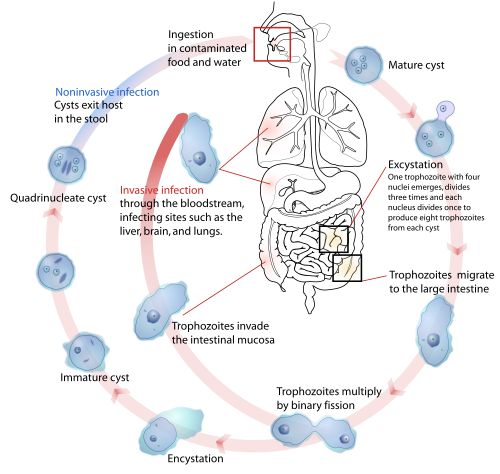

The life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica is simple and direct, involving a single host, humans. It consists of two main stages: the infective cyst stage and the trophozoite stage, each essential for the parasite’s survival, multiplication, and transmission.

Ingestion of Cysts

Infection begins when a person accidentally ingests mature quadrinucleate cysts through contaminated food, water, or fomites. In endemic regions, transmission is further facilitated by poor hygiene practices, open defecation, and the use of night soil as fertilizer. Flies and cockroaches can also act as mechanical vectors by carrying cysts from feces to food sources. The cysts are highly resistant to environmental conditions, allowing them to remain viable and infectious for prolonged periods.

Excystation

After passing through the acidic environment of the stomach, the cyst reaches the small intestine, where it undergoes excystation. Gastric secretions trigger the breakdown of the cyst wall, releasing a single quadrinucleate amoeba. This undergoes cytoplasmic division to form eight daughter trophozoites, which are motile and capable of colonizing the large intestine. The process of excystation is crucial for establishing intestinal infection and potential tissue invasion.

Multiplication and Colonization

The released trophozoites migrate to the colon, particularly the cecum and ascending colon, where they adhere to the intestinal mucosa. Colonization is facilitated by the parasite’s ability to bind host epithelial cells using specific surface lectins. Here, trophozoites multiply by binary fission, increasing their numbers rapidly. They may remain confined to the intestinal lumen, living harmlessly, or penetrate the mucosal lining, leading to invasive disease. The interaction with intestinal flora and host factors influences the outcome of colonization.

Encystation

When trophozoites are carried distally toward the dehydrating environment of the colon, they undergo encystation. This involves rounding up, eliminating food vacuoles, and developing a thick, protective cyst wall. The cytoplasm divides to form two, and later, four nuclei in mature cysts. Chromatoid bodies appear in immature cysts and gradually disappear as they mature. Encystation enables the parasite to survive outside the host, and mature cysts are excreted in the feces, completing the life cycle.

Environmental Survival and New Infection

Mature cysts excreted in formed stools are highly infective and can survive for several weeks under moist conditions. They are resistant to chlorination in routine water supplies, posing a challenge to public health control measures. Ingestion of these cysts by another host perpetuates the infection cycle, making contaminated food and water key vehicles for disease transmission.

Pathogenesis of Entamoeba histolytica

Entamoeba histolytica’s pathogenicity depends on its ability to invade tissues, lyse host cells, and evade immune defenses. Several virulence factors contribute to its capacity to cause intestinal and extraintestinal disease.

Mucosal Invasion

After adhering to the colonic mucosa, trophozoites secrete proteolytic enzymes, particularly cysteine proteinases, that degrade the mucus layer and epithelial cells. This breakdown of protective barriers facilitates deeper tissue invasion, resulting in characteristic flask-shaped ulcers. The ulcers start as small lesions on the mucosal surface and extend into the submucosa, where they broaden at the base. Continued tissue destruction can lead to secondary bacterial infection and complications such as perforation and peritonitis.

Erythrophagocytosis

A hallmark of invasive Entamoeba histolytica infection is the ingestion of erythrocytes by trophozoites. This process, termed erythrophagocytosis, is facilitated by surface lectins and is a distinguishing feature of pathogenic strains. Ingested erythrocytes within the cytoplasm indicate active tissue invasion and serve as a diagnostic clue during microscopic examination. Erythrophagocytosis also contributes to tissue damage and immune evasion by the parasite.

Formation of Amoeboma

Chronic infection may result in the development of an amoeboma, a granulomatous mass formed due to persistent inflammation and fibrosis. Amoebomas typically occur in the cecum or rectosigmoid colon and can clinically mimic colorectal carcinoma, causing diagnostic confusion. Patients with amoebomas may present with intestinal obstruction, abdominal pain, and bleeding per rectum. Histological examination is necessary to differentiate it from malignancy.

Extraintestinal Spread

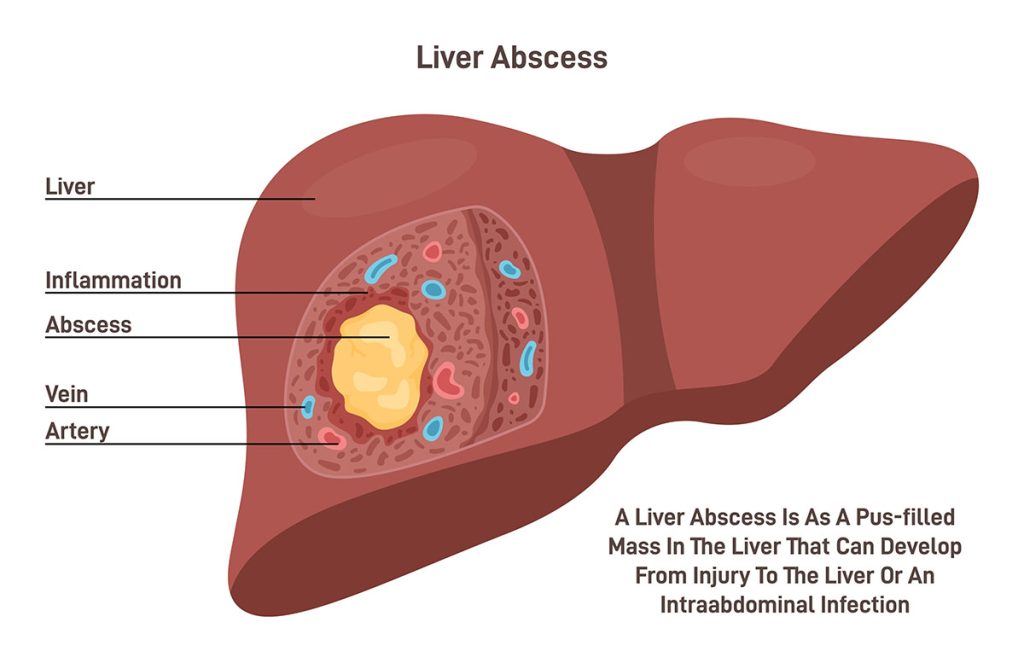

In severe cases, trophozoites penetrate the intestinal mucosa, enter the bloodstream, and disseminate to extraintestinal sites. The liver is the most common site, where they cause amoebic liver abscess characterized by localized necrosis and pus formation. Other less frequent sites include the lungs, brain, spleen, and skin. Spread to these sites can lead to serious complications, including pleuropulmonary amoebiasis and cerebral abscesses, both associated with high mortality rates if untreated.

Clinical Manifestations of Entamoeba histolytica Infection

The clinical manifestations of Entamoeba histolytica infection range from asymptomatic colonization to life-threatening invasive disease. The severity and nature of symptoms depend on host immunity, the virulence of the infecting strain, and the extent of tissue invasion. While many infections remain subclinical, symptomatic cases can present as intestinal or extraintestinal disease, each with characteristic clinical features.

Asymptomatic Carriers

A significant proportion of individuals infected with Entamoeba histolytica remain asymptomatic carriers. These individuals harbor the parasite in their colon without developing overt disease, acting as important reservoirs for transmission. Although asymptomatic, they continuously shed infective cysts in their feces, contributing to the persistence of the disease in endemic regions. Carriers usually experience no discomfort and are identified through stool examinations during epidemiological surveys or screening of household contacts.

Intestinal Amoebiasis

Intestinal amoebiasis typically manifests as amoebic dysentery or chronic diarrhea. Acute cases present with frequent, small-volume stools containing blood and mucus, accompanied by abdominal cramps, tenesmus, and urgency. Unlike bacterial dysentery, patients may have fewer systemic signs such as high fever. Chronic intestinal infection can lead to intermittent diarrhea, weight loss, fatigue, and abdominal tenderness. In rare cases, severe colitis may result in complications like toxic megacolon or intestinal perforation, both associated with high morbidity.

Amoebic Liver Abscess

Amoebic liver abscess is the most common extraintestinal manifestation of invasive amoebiasis. It occurs when trophozoites invade the portal circulation and localize in the liver, causing necrosis and abscess formation. Clinically, it presents with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever, chills, anorexia, and hepatomegaly. The abscess typically contains thick, brownish pus described as “anchovy sauce” in appearance, although it is sterile on culture due to the absence of bacteria. If untreated, the abscess may rupture into adjacent structures, leading to serious complications such as pleural or peritoneal infection.

Other Extraintestinal Manifestations

Less commonly, Entamoeba histolytica may spread to other organs such as the lungs, brain, spleen, and skin. Pulmonary amoebiasis results from direct extension of a liver abscess through the diaphragm or hematogenous spread, presenting with cough, chest pain, dyspnea, and expectoration of anchovy sauce-like sputum. Cerebral amoebiasis is rare but often fatal, characterized by seizures, altered consciousness, and focal neurological deficits. Cutaneous amoebiasis occurs through direct inoculation of trophozoites into skin lesions, producing painful ulcers with undermined edges.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica

Accurate laboratory diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica is essential for appropriate treatment and prevention of disease transmission. Various diagnostic techniques are available, including microscopic examination, serological tests, and advanced molecular methods.

Microscopy

Microscopic examination of stool samples remains the primary diagnostic method in resource-limited settings. Fresh, warm stool samples are preferred for detecting motile trophozoites, particularly those containing ingested erythrocytes. Saline and iodine wet mounts, along with permanent stained smears, are used for identifying cysts and trophozoites. Concentration techniques, such as formalin-ether sedimentation, improve detection rates, especially in cases with low parasite loads. However, microscopy has limited sensitivity and cannot reliably differentiate Entamoeba histolytica from morphologically similar non-pathogenic species like Entamoeba dispar.

Culture

Axenic and monoxenic culture systems allow the growth of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites from stool or tissue samples. While highly specific, culture is labor-intensive, time-consuming, and less commonly used in routine diagnostic laboratories. It is primarily employed in research settings for studying parasite biology, drug susceptibility, and virulence factors.

Serology

Serological tests detect anti-amoebic antibodies in serum, which are especially useful in diagnosing extraintestinal amoebiasis, where stool examination may be negative. Techniques such as indirect hemagglutination, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and immunofluorescence are commonly used. A positive serological test in a symptomatic patient from an endemic area strongly suggests invasive disease. However, antibodies may persist for months after infection, limiting their utility in differentiating current from past infections.

Antigen Detection

Detection of Entamoeba histolytica-specific antigens in stool, serum, or liver abscess pus using ELISA or rapid immunochromatographic assays improves diagnostic accuracy. These tests offer higher sensitivity and specificity than microscopy and help distinguish Entamoeba histolytica from non-pathogenic amoebae. Antigen detection is especially valuable in acute infections and for monitoring treatment response.

Molecular Techniques

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays are the most sensitive and specific diagnostic tools available for Entamoeba histolytica. They allow precise identification of the parasite and differentiation from morphologically identical species. PCR is applicable to stool, tissue, or abscess samples and is increasingly used in specialized laboratories and epidemiological studies. Despite its accuracy, the high cost and technical expertise required limit its widespread use in endemic regions.

Treatment of Entamoeba histolytica Infection

Effective treatment of Entamoeba histolytica infection involves the use of anti-amoebic drugs that target both the trophozoite and cyst stages. The choice of medication depends on whether the infection is asymptomatic, intestinal, or extraintestinal.

Luminal Amoebicides

For asymptomatic carriers and to eliminate luminal cysts after treating invasive disease, luminal amoebicides such as Diloxanide furoate, Paromomycin, or Iodoquinol are administered. These agents act locally in the intestinal lumen without systemic absorption, eradicating cysts and preventing further transmission. They are generally well-tolerated and effective in clearing infection when given in appropriate courses.

Tissue Amoebicides

In cases of intestinal amoebiasis or amoebic liver abscess, systemic tissue amoebicides like Metronidazole or Tinidazole are the drugs of choice. These nitroimidazole derivatives achieve high concentrations in tissues, killing invasive trophozoites. Metronidazole is administered orally or intravenously, depending on disease severity, and followed by a course of luminal amoebicide to prevent recurrence. Side effects include nausea, metallic taste, and a disulfiram-like reaction with alcohol.

Surgical Management

Surgical intervention is occasionally required in complicated cases, such as perforated colitis, large amoebomas causing obstruction, or liver abscesses at risk of rupture. Percutaneous aspiration or surgical drainage may be necessary for large or refractory liver abscesses. In such scenarios, prompt surgical management combined with anti-amoebic therapy improves outcomes and reduces mortality.

Conclusion

Entamoeba histolytica remains a significant public health challenge, particularly in areas with poor sanitation and hygiene. Its complex life cycle, involving resilient cysts and invasive trophozoites, facilitates both asymptomatic carriage and severe invasive disease. The organism’s ability to cause intestinal ulcers, amoebomas, and extraintestinal abscesses underscores the importance of early diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Advances in diagnostic techniques and effective therapeutic agents have improved outcomes, but prevention through improved sanitation, health education, and safe food and water practices remains crucial in controlling amoebiasis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Entamoeba histolytica?

Entamoeba histolytica is a parasitic protozoan that causes amoebiasis in humans, affecting the intestines and sometimes the liver.

How is Entamoeba histolytica transmitted?

It spreads through ingestion of contaminated food or water containing mature cysts, which then release trophozoites in the intestines.

What are the common symptoms of amoebiasis?

Typical symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea (sometimes with blood), fever, and in severe cases, liver abscess.

Related Contents

Classification of Virus – Necessity, Modern System and Importance