Foodborne pathogens continue to be a significant global public health issue, contributing to millions of illnesses, hospitalizations, and fatalities annually. Among these, Clostridium perfringens is a notorious bacterial agent responsible for one of the most commonly reported forms of foodborne gastroenteritis.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of C. perfringens, focusing on its classification, disease-causing mechanisms, symptoms, diagnostic methods, prevention strategies, and its impact on public health systems worldwide.

Table of Contents

Importance of Understanding Foodborne Pathogens

With modern food supply chains becoming increasingly global and complex, the risk of foodborne diseases has risen. Understanding the behavior, survival mechanisms, and control of pathogens like C. perfringens is vital for ensuring food safety, protecting public health, and maintaining consumer trust in food industries.

Accurate knowledge of these organisms aids in devising preventive measures, improving clinical management, and reducing the incidence of outbreaks linked to contaminated food products.

Prevalence of Clostridium perfringens in Foodborne Illnesses

Clostridium perfringens is one of the top five foodborne pathogens worldwide. Its ability to form heat-resistant spores allows it to survive typical cooking temperatures, making it a frequent cause of outbreaks, particularly in mass-catered events and institutions.

Outbreaks often involve improperly stored or inadequately reheated food, leading to rapid bacterial growth and toxin production that causes illness within hours of consumption.

What is Clostridium perfringens?

Clostridium perfringens is a gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium found widely in nature. Its versatility and resilience allow it to thrive in various environments, from soil to the human gastrointestinal tract, where it can act as both a harmless commensal and a dangerous pathogen.

Taxonomy and Classification

In biological taxonomy, C. perfringens belongs to:

- Domain: Bacteria

- Phylum: Firmicutes

- Class: Clostridia

- Order: Clostridiales

- Family: Clostridiaceae

- Genus: Clostridium

- Species: C. perfringens

Its classification is based on its anaerobic growth, ability to produce spores, and characteristic toxin profiles.

Morphology and Characteristics

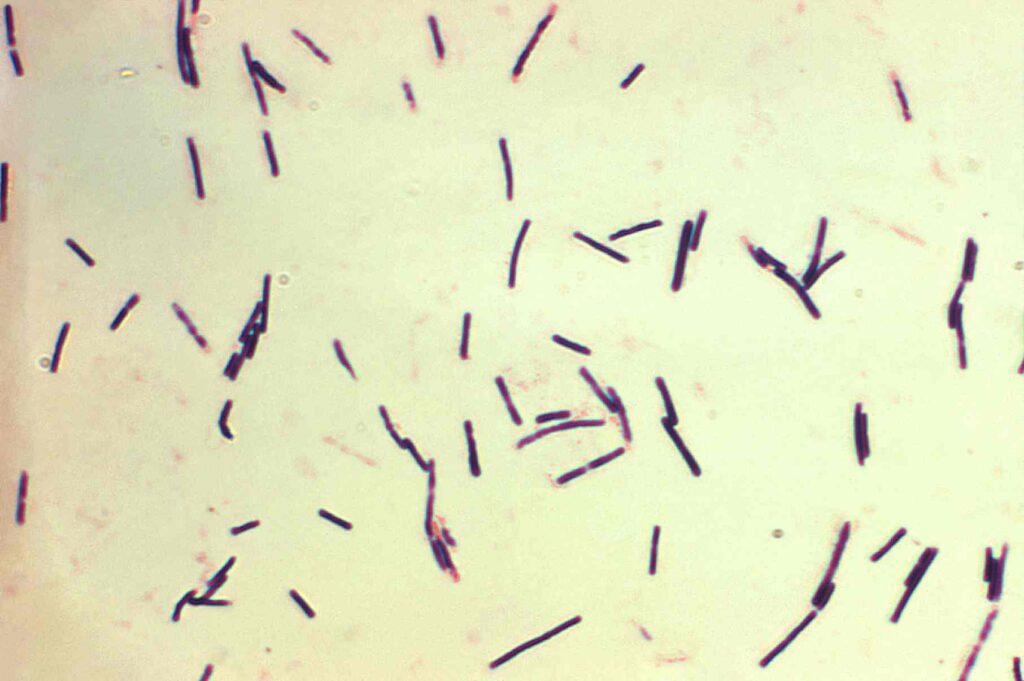

Microscopically, C. perfringens appears as large, rectangular, gram-positive rods. It is non-motile, lacks flagella, and produces central or sub-terminal oval spores, allowing it to survive adverse environmental conditions.

The bacterium grows rapidly under anaerobic conditions and can ferment a variety of carbohydrates, producing gas as a byproduct — a feature responsible for the gas gangrene seen in tissue infections.

Natural Habitats of C. perfringens

Clostridium perfringens naturally inhabits soil, decaying vegetation, sewage, marine sediments, and the intestinal tracts of humans and animals. Its spores can persist in environments for extended periods, becoming a persistent source of contamination in kitchens, food processing plants, and catering establishments.

Types of Clostridium perfringens

The bacterium is classified into several types based on the production of major toxins. This classification helps in understanding its clinical manifestations and epidemiology.

Classification Based on Toxin Production (Types A–E)

Clostridium perfringens strains are divided into five toxinotypes (A to E), depending on their production of four major toxins: alpha, beta, epsilon, and iota.

- Type A is the most common in human foodborne illnesses and gas gangrene.

- Types B, C, D, and E are primarily associated with animal infections but occasionally cause human diseases, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

Commonly Human-Associated Types

Type A strains are chiefly responsible for food poisoning outbreaks. They produce Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin (CPE), which directly damages the intestinal lining.

Type C is known to cause a rare but severe form of enteritis necroticans in humans, particularly in regions with protein-poor diets, such as parts of Papua New Guinea.

How Clostridium perfringens Causes Disease

The ability of C. perfringens to produce heat-resistant spores and a variety of potent toxins is central to its pathogenicity. Its disease-causing potential is closely linked to environmental conditions and the host’s immune status.

Life Cycle and Spore Formation

In adverse conditions, C. perfringens forms metabolically dormant endospores that can withstand heat, desiccation, and disinfectants. Once ingested, these spores germinate in the intestines under favorable conditions, multiplying rapidly and producing toxins.

This spore-forming ability makes the bacterium difficult to eradicate from food and environmental surfaces.

Environmental Triggers for Toxin Production

Toxin production in C. perfringens is influenced by environmental factors such as anaerobic conditions, warm temperatures, and nutrient availability. In food environments, improper storage or slow cooling allows rapid bacterial multiplication and enterotoxin formation.

In the intestines, changes in pH, bile salts, and oxygen levels can trigger enterotoxin synthesis, leading to foodborne illness.

Clostridium perfringens Enterotoxins

The primary virulence factor in foodborne illnesses caused by C. perfringens is the Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin (CPE). Its properties and mechanism of action have been extensively studied due to its public health importance.

Overview of CPE (Clostridium perfringens Enterotoxin)

CPE is a 35-kDa protein produced during sporulation in the intestinal tract. Once released, it binds to specific receptors on intestinal epithelial cells, forming pores that disrupt cellular ion balance, leading to diarrhea and cramping.

It is produced primarily by Type A strains associated with food poisoning outbreaks.

Mechanism of Action in the Intestine

CPE binds to claudin proteins in tight junctions of intestinal epithelial cells, creating pores in the cell membranes. This results in fluid and electrolyte leakage into the intestinal lumen, causing diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain.

Severe cases may lead to dehydration, especially in vulnerable populations like the elderly and young children.

Factors Influencing Toxin Production

Toxin production is affected by temperature, anaerobic conditions, and bacterial cell density. Suboptimal cooling of cooked food, particularly meat dishes, allows spores to germinate and proliferate, reaching concentrations sufficient to produce disease-causing levels of CPE.

C. perfringens and Food Poisoning

This pathogen is a leading cause of foodborne illness outbreaks, especially in institutional settings such as hospitals, schools, military camps, and large catered events.

How Food Becomes Contaminated

Contamination typically occurs when raw or undercooked meat products, stews, or gravies are prepared and then improperly stored. Spores survive initial cooking and, when cooled slowly, germinate and multiply.

Cross-contamination in kitchens and poor hygiene practices further facilitate the spread of spores to other food items.

Commonly Affected Foods

Foods most often associated with C. perfringens include:

- Cooked meat and poultry

- Gravies and meat-based sauces

- Stews and casseroles

- Pre-cooked dishes held at unsafe temperatures

Conditions Favoring Bacterial Growth

Clostridium perfringens thrives in anaerobic environments at temperatures between 20°C and 50°C, with optimum growth near 43°C. Foods left unrefrigerated for extended periods, especially in bulk or deep containers, create ideal conditions for rapid bacterial proliferation.

Symptoms of Clostridium perfringens Food Poisoning

Once ingested in contaminated food, C. perfringens spores or vegetative cells multiply in the intestine and release enterotoxins that irritate the gut lining. The resulting symptoms are typically gastrointestinal and can range from mild to severe based on bacterial load, toxin concentration, and individual susceptibility.

While most infections are self-limiting, prompt identification of symptoms is crucial for effective management and preventing complications in vulnerable groups.

Incubation Period

The incubation period for C. perfringens food poisoning is relatively short. Symptoms usually appear between 6 to 24 hours after consuming contaminated food, with an average onset of about 8–12 hours.

This brief incubation period is characteristic of toxin-mediated illnesses, where preformed toxins or rapidly produced toxins in the gut trigger immediate gastrointestinal effects.

Typical Clinical Symptoms

The most common symptoms of C. perfringens food poisoning include:

- Sudden onset of abdominal cramps

- Watery diarrhea without blood or mucus

- Occasional nausea and vomiting (less common compared to other foodborne illnesses)

In severe cases, individuals may experience dehydration, dizziness, or electrolyte imbalance, though fatalities are rare in healthy adults.

Duration and Severity

The illness is typically self-limiting, resolving within 12 to 24 hours without specific treatment. Symptoms tend to be milder than those caused by other foodborne pathogens like Salmonella or E. coli O157:H7.

However, prolonged or severe cases can occur in elderly, immunocompromised individuals, or those with underlying health conditions, necessitating medical intervention.

Diagnosis of C. perfringens Infections

Accurate diagnosis is essential for confirming outbreaks, guiding treatment, and implementing public health control measures. Diagnosis involves a combination of clinical assessment and laboratory confirmation through microbiological and molecular techniques.

Laboratory Identification Methods

Stool samples from affected individuals are cultured under anaerobic conditions to isolate C. perfringens. Growth is rapid, producing characteristic colonies on selective media such as Perfringens agar or Blood agar.

Microscopic examination, Gram staining, and biochemical tests help confirm the identity of the organism.

Stool Sample Analysis

Diagnosis often includes testing stool samples for high levels of C. perfringens. Detection of >10^6 colony-forming units (CFU) per gram of stool in symptomatic patients is considered diagnostic of foodborne illness caused by this organism.

In outbreak investigations, testing both patient samples and implicated food items strengthens epidemiological evidence.

Toxin Detection Techniques

The presence of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) in stool specimens confirms the cause of food poisoning. Techniques such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and latex agglutination are routinely used to detect CPE.

These tests provide rapid, sensitive, and specific results, enabling timely clinical and public health responses.

PCR and Molecular Assays

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays targeting the cpe gene offer a highly sensitive method for detecting toxin-producing strains of C. perfringens. PCR is particularly useful in complex outbreak situations and can also be applied to food samples.

Molecular methods enhance diagnostic accuracy and provide valuable information about strain types and their toxin profiles.

Treatment and Management

Management of C. perfringens food poisoning is primarily supportive, as the illness is self-limiting in most cases. Treatment focuses on relieving symptoms, preventing dehydration, and monitoring for complications in at-risk populations.

Supportive Care and Hydration

Oral rehydration with fluids and electrolytes is the mainstay of treatment for most patients. Commercial or homemade oral rehydration solutions (ORS) can help replace lost fluids and salts, minimizing the risk of dehydration.

In cases of severe fluid loss, particularly among the elderly or infants, intravenous (IV) fluids may be required.

When Antibiotics are Recommended

Antibiotics are rarely necessary for uncomplicated food poisoning cases caused by C. perfringens. However, in severe or systemic infections such as clostridial gas gangrene, prompt administration of penicillin, clindamycin, or metronidazole is essential.

Routine antibiotic use in foodborne cases is discouraged, as it can disrupt normal gut flora and promote antibiotic resistance.

Prognosis and Recovery Time

The prognosis for C. perfringens food poisoning is excellent in healthy individuals, with symptoms typically resolving within 24 to 48 hours. Complications are uncommon, although immunocompromised patients may require prolonged medical supervision.

Complete recovery is expected, and long-term effects are extremely rare.

Prevention of Clostridium perfringens Food Poisoning

Since C. perfringens foodborne illness is largely preventable, adhering to proper food safety practices at every stage — from food preparation to storage and serving is critical.

Proper Food Handling Practices

Good hygiene and sanitary food preparation conditions prevent initial contamination. This includes:

- Washing hands thoroughly before handling food

- Cleaning kitchen surfaces and utensils regularly

- Avoiding cross-contamination between raw and cooked foods

Cooking and Reheating Guidelines

Proper cooking kills vegetative cells of C. perfringens, but spores can survive. To reduce risk:

- Cook meats thoroughly to safe internal temperatures

- Avoid leaving cooked food at room temperature for extended periods

- Rapidly cool leftovers to below 5°C and reheat to at least 74°C before consumption

Large batches of food should be divided into shallow containers for quicker, even cooling.

Importance of Food Storage Temperatures

Temperature control is one of the most effective ways to prevent C. perfringens growth. Food should not be kept between 20°C and 50°C for more than two hours. Refrigeration inhibits bacterial multiplication, while reheating eliminates any vegetative cells.

Commercial kitchens and catering services must use temperature-monitoring systems to ensure food safety compliance.

Outbreaks and Public Health Impact

Clostridium perfringens food poisoning outbreaks are common worldwide, often linked to mass catering events, hospitals, military facilities, and schools. Though typically mild, these outbreaks can affect large groups rapidly.

Notable Documented Outbreaks Worldwide

Notable outbreaks include large-scale incidents in the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom. A famous U.S. outbreak in the 1970s affected over 1000 school children, highlighting the importance of institutional food safety.

More recent incidents in elderly care homes and hospital settings underline the risk to vulnerable populations when food is improperly stored or reheated.

Economic and Health Burden of C. perfringens Outbreaks

Although rarely fatal, C. perfringens outbreaks incur significant healthcare costs, productivity losses, and public health response expenses. They strain healthcare systems during peak seasons and cause public concern, especially when involving high-risk institutions.

The economic burden includes diagnostic testing, outbreak investigation, food disposal, and compensation in severe cases.

Modern Research and Advances

Continuous research aims to develop improved preventive, diagnostic, and therapeutic strategies against C. perfringens infections, particularly given the bacterium’s resilience and potential to cause large outbreaks.

Vaccine Development Efforts

Although no vaccine exists for foodborne C. perfringens illness in humans, animal vaccines targeting specific toxin types have been developed for veterinary use. Human vaccine research is ongoing, focusing on CPE-neutralizing antibodies and inactivated toxins.

Potential vaccines could protect at-risk populations, such as hospital patients and military personnel, from severe clostridial infections.

Rapid Detection Methods for Food Safety

Modern techniques, including real-time PCR, biosensors, and immunochromatographic assays, enable rapid detection of C. perfringens in food products. These methods improve outbreak control by facilitating timely public health interventions and food recalls.

Integration of such technologies in food safety monitoring programs is expected to enhance consumer protection and industry compliance.

Ethical and Regulatory Aspects

Ensuring food safety involves not only scientific vigilance but also ethical responsibility and regulatory oversight. Balancing technological capabilities with public health needs is crucial for ethical management of foodborne pathogen risks.

Food Industry Regulations and Standards

Food safety authorities like the World Health Organization (WHO), U.S. FDA, and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) set microbiological criteria for food products, particularly ready-to-eat items. These regulations mandate safe cooking, storage, and hygiene practices.

Regular inspection, staff training, and documentation of food safety protocols are essential components of legal compliance.

Reporting and Public Health Response

Prompt reporting of suspected foodborne illnesses is vital for public health surveillance. Health departments investigate outbreaks, trace food sources, and implement control measures to prevent recurrence.

Public awareness campaigns and food industry audits further reinforce the importance of strict food safety practices at every stage of food handling.

Conclusion

Clostridium perfringens remains a significant contributor to global foodborne illnesses, particularly in institutional settings and mass catering operations. Its resilience through spore formation and rapid toxin production make it a persistent threat to public health.

Effective prevention hinges on strict adherence to food hygiene, temperature control, and proper handling practices. Advances in detection methods, vaccine development, and public health policies offer promise in reducing the burden of this pathogen.

Ongoing education, research, and surveillance are key to safeguarding food safety and protecting vulnerable populations from preventable outbreaks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What foods most commonly cause Clostridium perfringens food poisoning?

Cooked meats, poultry, gravies, stews, and casseroles, especially when cooked in large batches and kept at unsafe temperatures.

How quickly do symptoms appear after ingestion?

Symptoms usually appear 6 to 24 hours after eating contaminated food, typically around 8–12 hours.

Is Clostridium perfringens food poisoning contagious?

No, it’s not contagious. It spreads through contaminated food, not person-to-person contact.

Related Contents

Chromosomes- Definition, Structure, Types, Model, Functions

CLED Agar- Composition, Principle, Preparation, Results, Uses