Bacteroides are a group of obligate anaerobic, Gram-negative, non-spore-forming bacteria commonly found in the human gastrointestinal tract. They play an important role in maintaining the balance of the gut microbiota and assisting in the digestion of complex molecules. However, under certain circumstances, such as when they translocate from their normal habitat to sterile body sites, Bacteroides species can cause opportunistic infections. Understanding their classification, virulence mechanisms, identification through biochemical tests, and clinical behavior is essential in clinical microbiology.

Summary of Bacteroides

- Bacteroides are Gram-negative, anaerobic bacteria normally found in the gut.

- They cause opportunistic infections when they escape into sterile body sites.

- Key identification tests include bile resistance, catalase test, and nitrate reduction.

Table of Contents

Classification of Bacteroides

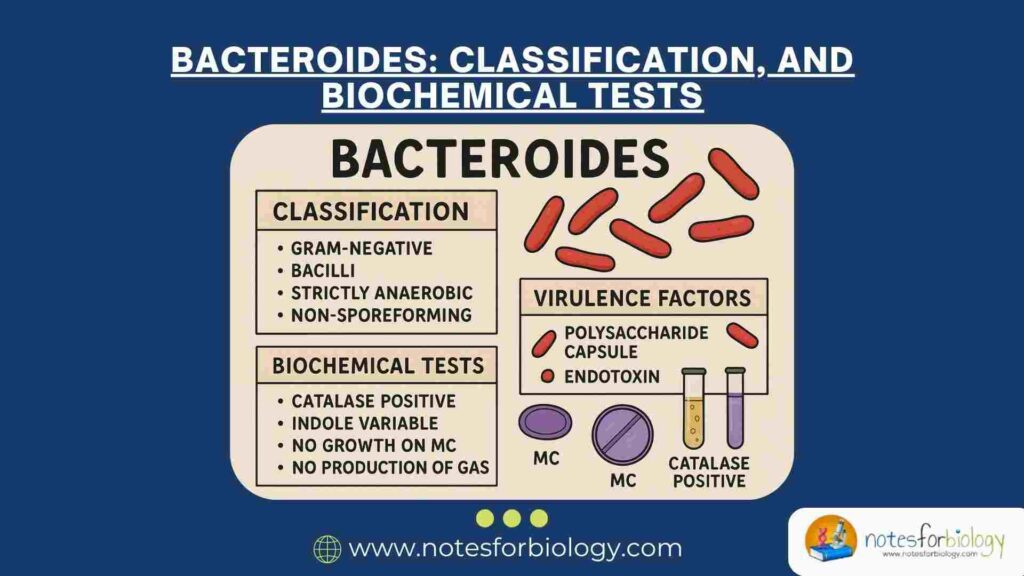

The classification of Bacteroide is based on their morphological, physiological, and genetic characteristics. These bacteria belong to a distinct taxonomic hierarchy within the domain of prokaryotes.

Domain and Phylum

Bacteroide are classified under the domain Bacteria. They belong to the phylum Bacteroidetes, which consists of a large group of Gram-negative, non-sporulating, and rod-shaped bacteria, many of which are found in animal and human gastrointestinal tracts.

Class and Order

Within the phylum Bacteroidetes, Bacteroide are placed under the class Bacteroidia. This class comprises strictly anaerobic bacteria that are predominantly saccharolytic and resistant to bile salts. They are further classified under the order Bacteroidales.

Family and Genus

The order Bacteroidales includes the family Bacteroidaceae, to which the genus Bacteroides belongs. This genus includes several species, many of which are commensals of the human intestinal flora, while a few are opportunistic pathogens.

Common Species

Among the notable species of Bacteroide, Bacteroides fragilis is the most clinically significant, often associated with intra-abdominal infections, abscesses, and bloodstream infections. Other important species include Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides vulgatus, and Bacteroides ovatus, each of which contributes to the complex microbial ecology of the gut.

Morphological Characteristics

Bacteroide species are Gram-negative, meaning they do not retain the crystal violet stain during Gram staining. They appear as pale pink rods under the microscope. These bacteria are typically pleomorphic, exhibiting variable shapes ranging from rods to coccoid forms. Bacteroides are non-spore-forming and generally non-motile, although some species may possess flagella. Their cell wall contains lipopolysaccharide (LPS), but unlike other Gram-negative bacteria, their LPS has low endotoxic activity.

Cultural Characteristics

Bacteroides are obligate anaerobes, meaning they grow only in environments devoid of oxygen. On anaerobic blood agar plates, colonies of Bacteroides fragilis appear as circular, convex, and smooth, usually grayish and non-hemolytic. Some species may produce a characteristic foul odor due to the production of volatile fatty acids during metabolism. These bacteria are bile-resistant and can grow in the presence of 20% bile, which helps differentiate them from other anaerobes.

Virulence Factors of Bacteroides

Although many Bacteroides species are commensal organisms, certain virulence factors enable them to cause disease when they access normally sterile areas of the body. These factors contribute to colonization, tissue invasion, immune evasion, and damage to host tissues.

Capsule Formation

One of the most significant virulence factors of Bacteroides is its polysaccharide capsule. The capsule enhances the bacteria’s ability to evade phagocytosis by host immune cells. It also promotes abscess formation by stimulating an inflammatory response that walls off the bacteria from surrounding tissues.

Production of Enzymes

Bacteroide species produce various extracellular enzymes, including hyaluronidase, neuraminidase, collagenase, and proteases. These enzymes degrade host tissues and extracellular matrix components, facilitating bacterial invasion and spread within the host. Hyaluronidase, for example, breaks down hyaluronic acid in connective tissue, while collagenase degrades collagen fibers.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

The outer membrane of Bacteroide contains a modified form of lipopolysaccharide. Unlike the LPS of other Gram-negative bacteria, the endotoxic activity of Bacteroides LPS is considerably lower. However, it still plays a role in eliciting inflammatory responses and contributes to the pathogenesis of infections.

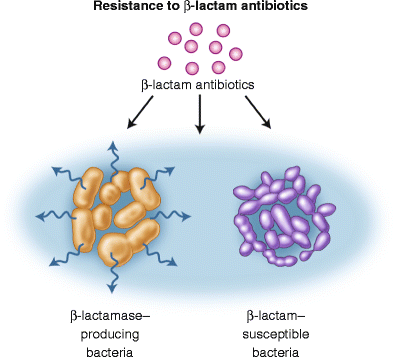

Beta-Lactamase Production

Many strains of Bacteroides, especially Bacteroides fragilis, produce beta-lactamase enzymes that confer resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins and cephalosporins. This enzymatic activity makes the treatment of infections caused by Bacteroides more challenging, necessitating the use of beta-lactamase inhibitors or alternative antibiotics.

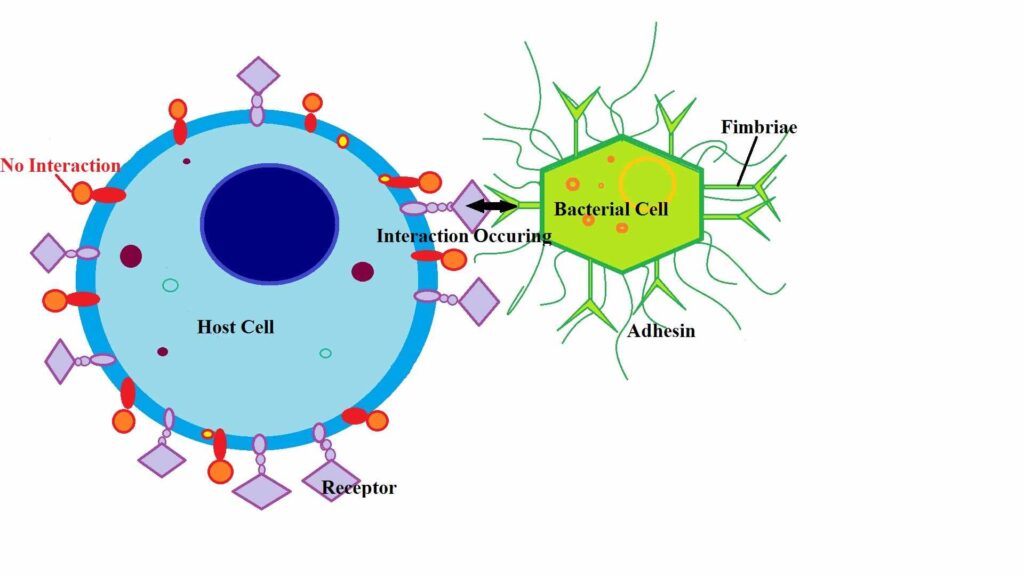

Fimbriae and Adhesins

Bacteroides possess surface structures such as fimbriae and adhesins that facilitate their attachment to host cells, extracellular matrices, and other bacteria. This adherence is crucial for colonization, biofilm formation, and evasion of host defenses.

Biochemical Tests for Identification of Bacteroides

Accurate identification of Bacteroide species in clinical specimens relies on a combination of morphological observation, anaerobic culture, and specific biochemical tests. These tests assess the metabolic and enzymatic capabilities of the organism.

Catalase Test

Most species of Bacteroide, particularly Bacteroides fragilis, are catalase-positive. In this test, the presence of the enzyme catalase is determined by adding hydrogen peroxide to a bacterial culture. The appearance of bubbles due to the release of oxygen indicates a positive result.

Indole Test

The ability to produce indole from the amino acid tryptophan varies among Bacteroide species. Bacteroides fragilis is typically indole-negative, while other species such as Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron may yield a positive result. Indole production is detected by adding Kovac’s reagent, which produces a red ring in the presence of indole.

Bile Esculin Test

Bacteroides fragilis group bacteria can hydrolyze esculin in the presence of bile salts. In this test, the organism is inoculated onto bile esculin agar. A positive reaction is indicated by the blackening of the medium due to the formation of iron salts from hydrolyzed esculin.

Nitrate Reduction Test

Bacteroide species possess the ability to reduce nitrate to nitrite. This characteristic is tested by adding nitrate broth to the culture and subsequently detecting nitrite with specific reagents. A positive result is indicated by a color change after the addition of reagents or the appearance of gas bubbles.

Sugar Fermentation Tests

Bacteroides can ferment a variety of carbohydrates, producing acid as an end product. Commonly tested sugars include glucose, lactose, and maltose. The fermentation pattern helps differentiate between species, as Bacteroides fragilis ferments glucose but not lactose.

Resistance to Bile

A key distinguishing feature of the Bacteroides fragilis group is their ability to grow in the presence of 20% bile salts. This characteristic aids in their identification and differentiation from other anaerobic bacteria.

Clinical Presentation of Bacteroide Infection

The clinical presentation of infections caused by Bacteroide species varies depending on the site of infection, the severity of the disease, and whether it occurs alone or in association with other pathogens. Most Bacteroide infections are endogenous in origin, arising when the normal mucosal barrier is disrupted.

Intra-abdominal Infections

One of the most common manifestations of Bacteroides infection is intra-abdominal infection. These may result from perforation of the gastrointestinal tract due to appendicitis, diverticulitis, peptic ulcer disease, or traumatic injuries. Clinical symptoms include abdominal pain, tenderness, distension, fever, and signs of peritonitis. If untreated, localized abscesses may form within the peritoneal cavity.

Pelvic Infections

Infections of the female pelvic region, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), tubo-ovarian abscesses, and post-surgical pelvic abscesses, frequently involve Bacteroide species, especially Bacteroides fragilis. Clinical signs typically include lower abdominal pain, fever, abnormal vaginal discharge, and tenderness during pelvic examination.

Soft Tissue and Skin Infections

Bacteroides can contribute to necrotizing soft tissue infections, cellulitis, and infected wounds, especially after trauma, surgery, or animal bites. These infections often produce foul-smelling purulent discharge due to anaerobic metabolism. The affected area may exhibit swelling, redness, pain, and signs of necrosis.

Bacteremia

Although less common, Bacteroide species can enter the bloodstream, leading to bacteremia. This condition often originates from intra-abdominal, pelvic, or soft tissue infections. Clinical features include high-grade fever, chills, hypotension, and signs of septicemia. Bacteroides bacteremia is associated with high mortality, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Central Nervous System (CNS) Infections

Bacteroide infections involving the central nervous system, such as brain abscesses, are rare but serious. These infections typically result from the extension of infections from nearby structures like the ears, sinuses, or teeth, or through hematogenous spread. Clinical symptoms may include headache, fever, neurological deficits, seizures, and altered mental status.

Pulmonary Infections

Aspiration pneumonia, lung abscesses, and empyema may involve Bacteroide species, particularly in individuals with poor oral hygiene or those who aspirate oropharyngeal contents. Patients may present with cough, foul-smelling sputum, fever, chest pain, and signs of respiratory distress.

Patient History in Bacteroide Infection

A thorough clinical history is crucial in the evaluation of suspected Bacteroide infections. It helps identify risk factors, possible sources of infection, and the progression of symptoms.

Recent Surgical Procedures

Patients who have undergone recent abdominal, pelvic, or dental surgeries are at an increased risk of Bacteroide infections. These bacteria can invade sterile body sites during surgical interventions, especially when mucosal surfaces are breached.

History of Trauma

Traumatic injuries, particularly those involving penetration of the gastrointestinal tract or soft tissues, can introduce Bacteroides into sterile areas, leading to infection. Such incidents should be carefully noted in the patient’s history.

Underlying Medical Conditions

Chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, malignancy, and immunosuppression predispose individuals to severe anaerobic infections. Immunocompromised patients may present with atypical or more severe forms of Bacteroide infections.

Use of Invasive Devices

The use of devices such as intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs) or intraperitoneal catheters increases the risk of pelvic and intra-abdominal infections by facilitating bacterial entry.

Dental and Oropharyngeal Infections

Poor dental hygiene, dental abscesses, or recent dental procedures can lead to Bacteroides-associated head and neck infections or aspiration pneumonia, particularly in individuals with impaired swallowing mechanisms.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Conditions such as diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and perforated peptic ulcers may allow the translocation of Bacteroides from the gut lumen into the peritoneal cavity, causing peritonitis and abscess formation.

Causes of Bacteroide Infection

Bacteroide infections typically occur when the normal mucosal barriers are breached, allowing these anaerobic organisms to invade sterile body sites. Several factors contribute to the pathogenesis of these infections.

Mucosal Barrier Disruption

The integrity of mucosal surfaces, particularly in the gastrointestinal and female genital tracts, is vital in preventing the translocation of Bacteroide species. Surgical procedures, traumatic injuries, ulceration, or inflammatory conditions can compromise these barriers, leading to infection.

Polymicrobial Synergy

Bacteroides often participate in mixed infections alongside facultative anaerobes such as Escherichia coli and other anaerobes like Peptostreptococcus and Fusobacterium. The synergistic interaction among these bacteria enhances their collective virulence, impairs host defenses, and promotes abscess formation.

Immunosuppression

Patients with weakened immune systems, due to conditions like HIV/AIDS, malignancy, organ transplantation, or chemotherapy, are more susceptible to Bacteroide infections. In these individuals, the innate and adaptive immune responses are compromised, allowing opportunistic pathogens to thrive.

Antibiotic Selection Pressure

Prolonged or inappropriate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics can disrupt the normal gut flora balance, leading to overgrowth and translocation of resistant anaerobic bacteria like Bacteroides. Beta-lactamase production by Bacteroides fragilis contributes to its survival and pathogenicity in such environments.

Aspiration of Oropharyngeal Contents

In individuals with altered consciousness, neurological impairment, or poor oral hygiene, aspiration of saliva and oropharyngeal secretions can introduce Bacteroides into the lower respiratory tract. This may result in aspiration pneumonia, lung abscesses, and empyema.

Invasive Medical Devices

The introduction of foreign bodies such as intrauterine devices or abdominal drains can serve as a nidus for anaerobic infections by allowing bacteria access to sterile tissues. Infections associated with these devices are often persistent and require both antimicrobial and surgical interventions.

Conclusion

Bacteroide represent a significant group of anaerobic, Gram-negative bacteria, primarily residing in the human intestinal tract as part of the normal flora. While typically harmless within their natural habitat, these organisms possess various virulence factors enabling them to cause serious opportunistic infections when displaced. Understanding their classification, morphological and cultural traits, virulence mechanisms, and the biochemical tests employed for their identification is essential for diagnosing and managing anaerobic infections effectively. Their notable resistance to antibiotics underscores the importance of accurate laboratory identification and susceptibility testing in clinical microbiology.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the function of Bacteroides?

Bacteroides help in breaking down complex carbohydrates and producing beneficial short-chain fatty acids in the human gut.

What disease is caused by Bacteroides?

Bacteroides can cause intra-abdominal infections, abscesses, peritonitis, and bacteremia, especially after intestinal injury or surgery.

Where are Bacteroides found?

Bacteroides are commonly found in the human intestinal tract, particularly in the colon, as part of the normal gut flora.