Bacillus cereus is a gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium commonly found in soil, food, and even marine sponges. While some strains are beneficial, others can cause foodborne illness in humans due to their toxin-producing nature and ability to form spores. Although B. cereus is most frequently linked to food poisoning, the bacterium can also induce post-traumatic ophthalmitis, which has to be treated locally quickly and aggressively.

The organism is present in most uncooked foods, especially grains like rice, and is widely distributed in the environment. One of two enterotoxins mediates B. cereus-induced gastroenteritis. The diarrheal type of the illness is brought on by the heat-labile enterotoxin, which activates the intestinal epithelial cells’ adenylate cyclase–cyclic adenosine monophosphate pathway, resulting in copious amounts of watery diarrhea.

Table of Contents

Habitat of Bacillus cereus

Soil, vegetables, milk, cereals, spices, fried rice, cooked meats and poultry, soups, and desserts are all sources of Bacillus cereus isolation.

Inappropriate food handling locations include mashed potatoes, beef stew, apples, hot chocolate offered in vending machines, and other items. Frankland separated B. cereus from air in a cowshed in 1887. It is a Bacillus species that is saprophytic. Spores and vegetative cells are abundant in the natural world. For immunocompromised individuals, they are opportunistic infections, occasionally human pathogens. It is not thought to be a typical human flora, yet it may sometimes colonize the skin, gastrointestinal system, or respiratory tract.

It is an intestinal symbiont of arthropods and may also be found in the microflora of invertebrates. In termites, roaches, and sowbugs, it grows filamentously. Alcohol does not readily destroy Bacillus cereus; in fact, it has been seen that large enough colonies of the bacteria may infect distilled liquors, swabs, and pads soaked in alcohol. Although B. cereus can be found in normal stool specimens, a concentration of 105 bacteria or more per gram of food is considered diagnostic. Therefore, the presence of B. cereus in a patient’s feces alone is not sufficient to make a diagnosis of B. cereus.

Morphology of Bacillus cereus

- It is not thought to be a typical human flora, yet it may sometimes colonize the skin, gastrointestinal system, or respiratory tract.

- When exposed to physical and chemical stimuli including heat, cold, desiccation, radiation, disinfection, antibiotics, and other poisons, endospores exhibit a far higher degree of resistance.

- It can grow in both oxygen-rich and oxygen-deficient environments.

- It engages in interactions with other microbes in the rhizosphere, which is the area that surrounds plant roots.

- It is an intestinal symbiont of arthropods and may also be found in the microflora of invertebrates. In termites, roaches, and sowbugs, it grows filamentously.

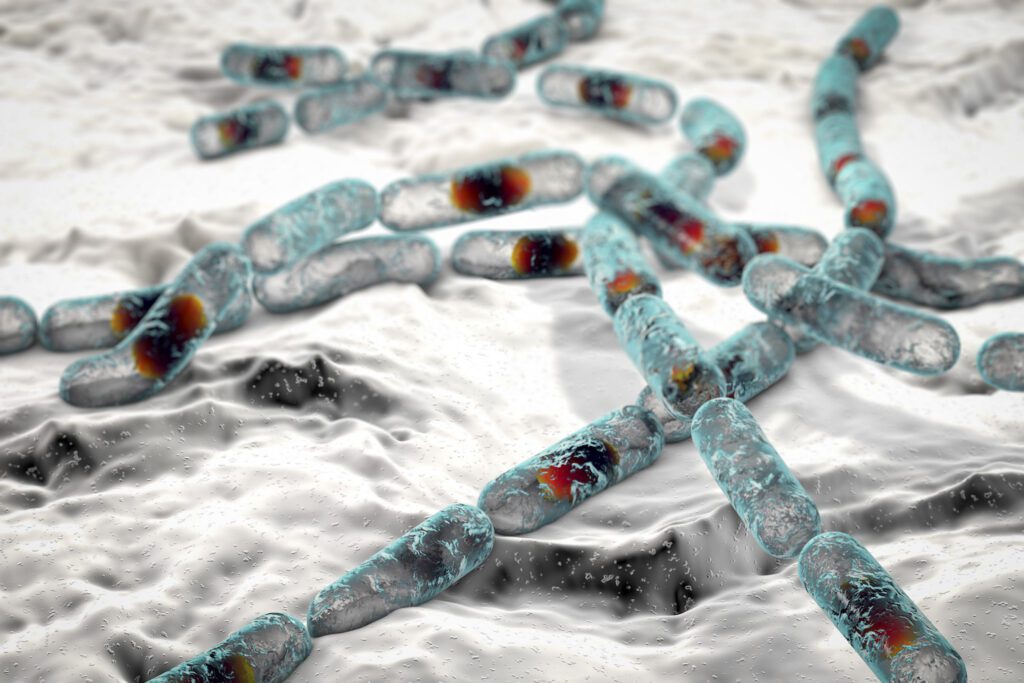

- Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacilli with square ends are called Bacillus cereus.

- increasing age may occasionally look gram-variable or even gram-negative.

- They come in short chains or are formed like a single rod.

- Chain members’ clean, well-defined connections are readily seen.

- The staining of a tissue segment may seem filamentous and lengthy.

Structure of the Genome

The circular chromosome measures 5,411,809 nucleotides. It has 5366 RNA operons, 147 structural RNA, 5234 proteins that code for them, and 5481 genes. The plasmid has a size of 5–500 kb.

Characteristics of Bacillus cereus

The majority of Bacillus species thrive easily on peptone or nutrient agar medium. Its ideal temperature range for growth is 20°C to 40°C, with 37°C being the most common. Being mesophilic, B. cereus may thrive in a variety of environmental settings. It develops big (2–5 mm) grey-white, granular colonies on Nutrient Agar at 37°C.

The colonies have less of a membranous consistency and a wavy edge. B. cereus colonies are big, feathery, dull, grey, granular, spreading, and opaque, with a rough matted surface and uneven perimeters on 5% sheep blood agar at 37°C. It is beta-hemolytic on blood agar. The erratic colony perimeters show how swarming occurred from the original inoculation location, possibly as a result of B. cereus swarming motility.

Clinical manifestation of Bacillus cereus

Food poisoning

1. Emetic Form

Eating tainted rice causes the disease’s emetic phase to manifest. The heat-resistant spores survive the initial boiling of the rice, but the majority of germs are destroyed. The spores germinate and the germs might grow quickly if the cooked rice is not refrigerated. Reheating the rice does not eliminate the heat-stable enterotoxin that is produced.

The enterotoxin, not the bacteria, is what causes the intoxication that is the emetic aspect of the illness. As a result, both the illness’s incubation time (one to six hours) and duration (less than 24 hours) are brief following consumption of the tainted rice. Abdominal pains, nausea, and vomiting are among the symptoms. Diarrhea and fever are usually absent.

2. Form of diarrhea

When B. cereus food poisoning manifests as diarrhea, it is a real infection that is brought on by eating tainted meat, vegetables, or sauces. The organism multiplies in the patient’s digestive system throughout a protracted incubation period, after which the heat-labile enterotoxin is released. The nausea, cramping in the abdomen, and copious watery diarrhea are caused by this enterotoxin.

Eye infections

Ocular infections caused by B. cereus typically develop following severe, penetrating eye injuries caused by objects contaminated with dirt. These consist of endophthalmitis and severe keratitis.

Other infections

B. cereus has been linked to both systemic and localized infections, including pneumonia, endocarditis, catheter-associated bacteremia, infections of the central nervous system, osteomyelitis, and wound infections. These infections are made more likely by the use of intravenous drugs or the presence of medical devices.

Treating Bacillus cereus

Individuals suffering from food poisoning caused by B. cereus simply need supportive care.

For individuals with severe dehydration, oral rehydration or, rarely, intravenous fluid and electrolyte replacement is recommended. There is no need for antibiotics. Antibiotic treatment is necessary for patients with the invasive illness. Tetracycline, aminoglycosides, vancomycin, erythromycin, and clindamycin can all be harmful to Bacillus cereus. It is resistant to trimethoprim and penicillin.

Prevention and Control of Bacillus cereus

Proper food handling practices can easily avert vomiting and diarrheal intoxications caused by this pathogen.

Rice that has been cooked and left overnight should be refrigerated rather than kept at room temperature, while meat and vegetables should not be kept at temperatures between 10 and 45 °C for extended periods. Good practice is essential for preventing infection in patients recovering from surgery, in immunocompromised individuals, and in individuals who are prone to infection in general.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Bacillus cereus?

Bacillus cereus is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacterium that is commonly found in soil and food. It is known for causing foodborne illnesses and spoilage.

Where is Bacillus cereus commonly found?

Bacillus cereus is commonly found in soil, dust, and vegetation. It can also be present in various foods, particularly rice, pasta, dairy products, and spices.

Can Bacillus cereus form spores?

Yes, Bacillus cereus forms highly resistant endospores that can survive harsh conditions such as heat, desiccation, and disinfectants. Spores can germinate into vegetative cells under favourable conditions.

Related Articles