Introduction

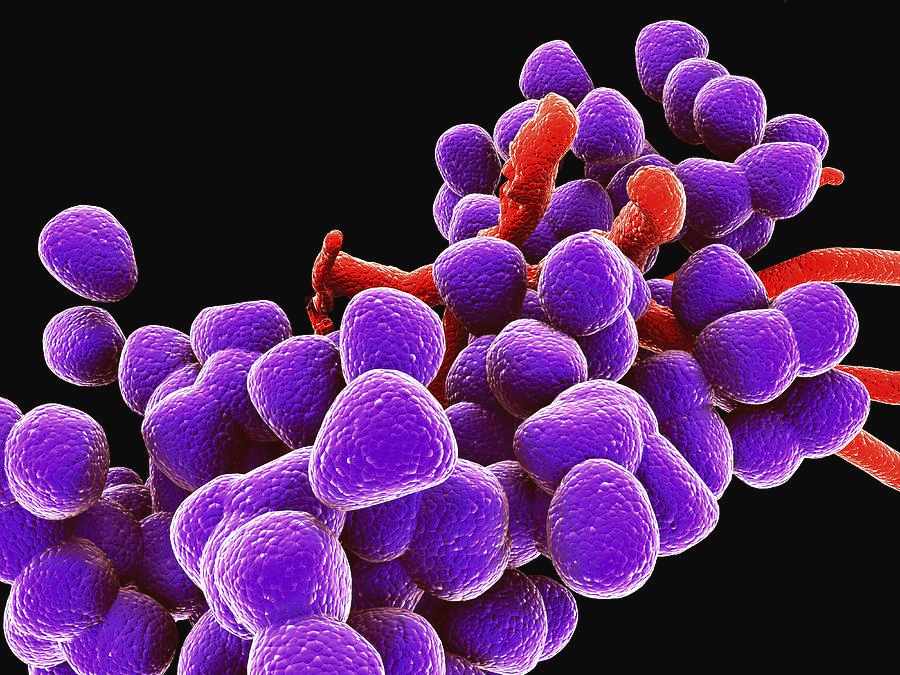

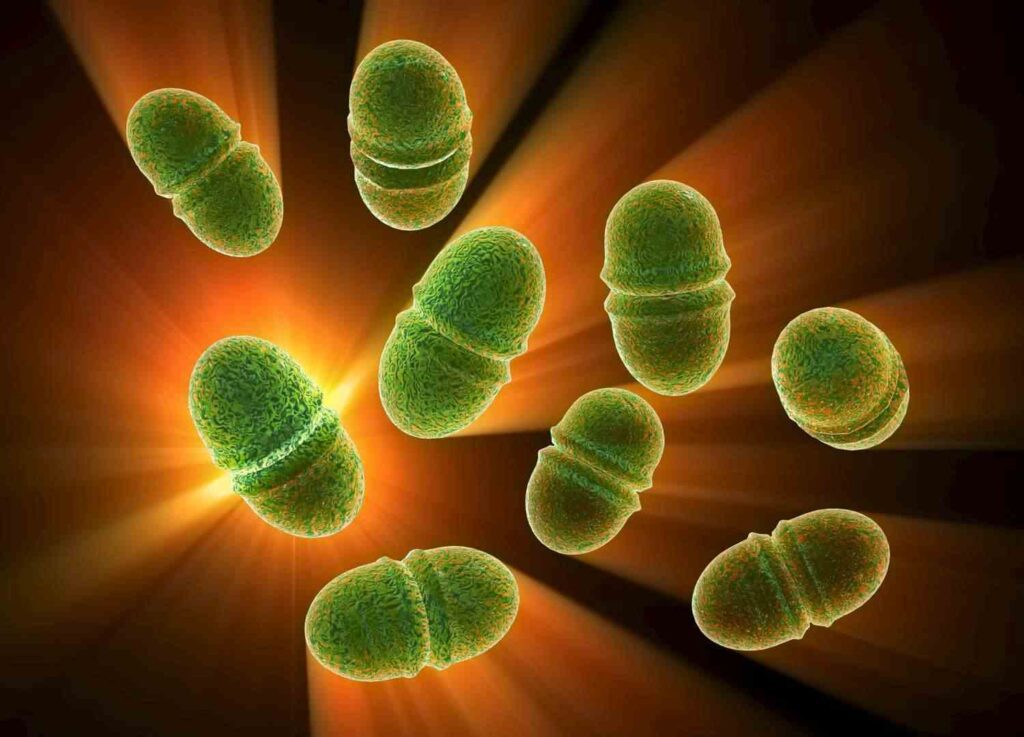

Enterococcus faecalis is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic bacterium that naturally lives in the human gastrointestinal tract. It generally coexists peacefully with our body, performing useful roles in digestion and microbial balance. However, in certain situations, especially when a person’s immune system is weak or if they are hospitalized, this bacterium can change from being harmless to harmful. It can become opportunistic, meaning it takes advantage of the weakened body defenses and causes infections. What makes E. faecalis especially concerning is its strong resistance to many commonly used antibiotics. This trait allows it to survive even after antibiotic treatments, making it a growing concern in hospitals and other healthcare environments.

Learning about E. faecalis is important for microbiologists, doctors, nurses, and students in the medical field. This guide aims to explain in a simple and clear way everything you need to know about this bacterium—from its appearance and where it lives to how it causes disease, how it can be treated, and how we can prevent it from spreading.

Table of Contents

Morphology and Characteristics

Enterococcus faecalis has several specific features that help scientists and doctors identify it easily in the lab. Here are its main characteristics, explained in simple terms:

- Gram-positive cocci: These are round-shaped bacteria that stain purple in a Gram stain test. They usually appear in pairs or small chains under a microscope.

- Non-spore forming: Unlike some bacteria that produce spores to survive tough conditions, E. faecalis does not form spores.

- Non-motile: It does not have flagella or any other structures to move around.

- Facultative anaerobe: This means it can survive with or without oxygen, giving it the ability to live in different parts of the body.

- Catalase-negative: It does not produce the enzyme catalase, which breaks down hydrogen peroxide.

- Tolerates high salt concentration: It can grow in environments that have high salt levels, such as 6.5% sodium chloride.

- Grows in bile esculin medium: It can survive in the presence of bile and breaks down a substance called esculin, turning the medium black.

- Temperature adaptability: It can grow in a wide temperature range, from as low as 10°C to as high as 45°C.

These properties help in identifying E. faecalis in clinical laboratories.

Natural Habitat

E. faecalis naturally exists in the following areas:

- Human and animal intestines: It is a normal part of the gut microbiome and helps with digestion.

- Mouth: Sometimes found in the saliva and oral cavity.

- Vagina: It may be present as part of the normal flora.

- Environment: Found in soil, water, and various foods due to its hardy nature.

In the intestine, E. faecalis generally behaves well, coexisting with other microbes. But when the balance is disturbed—like during illness, antibiotic use, or surgeries—it may move to other body parts and cause infections.

Pathogenicity and Virulence Factors

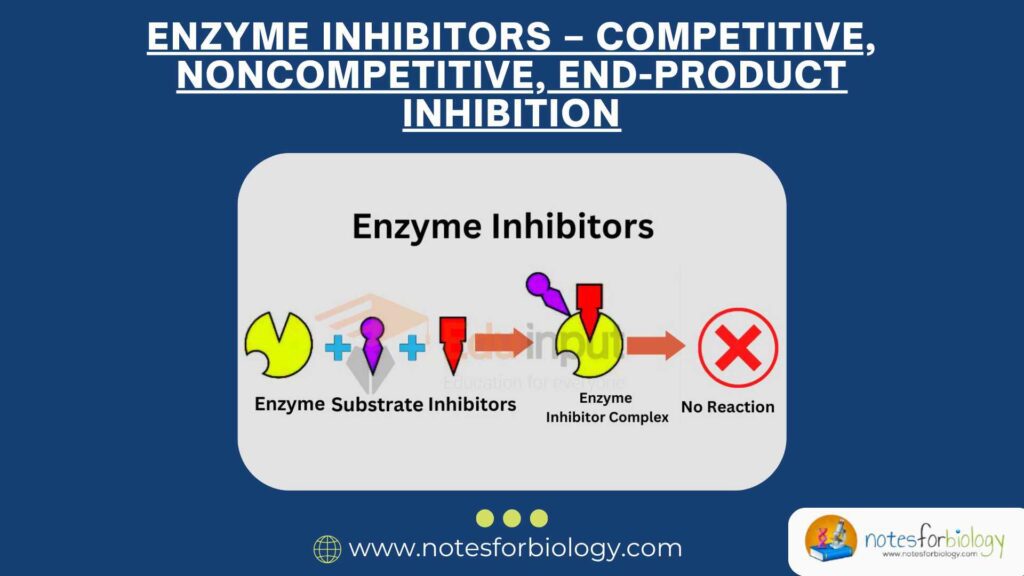

E. faecalis is usually harmless, but under certain conditions, it can become dangerous. It is known as an opportunistic pathogen because it mainly causes problems when the body’s immune defenses are down. Several traits, called virulence factors, make it capable of causing disease:

- Aggregation substance: A sticky surface protein that allows bacteria to clump together and attach to human cells, especially in areas like the urinary tract or heart valves.

- Cytolysin: A harmful protein (toxin) that kills human cells, helping the bacteria invade tissues.

- Gelatinase: An enzyme that breaks down proteins in the host, making it easier for the bacteria to spread.

- Biofilm formation: E. faecalis can form a protective layer, or biofilm, on medical devices like catheters and heart valves. This makes it very hard to remove and protects it from antibiotics.

- Adhesins: Surface molecules that help the bacteria stick to cells in the human body, especially epithelial cells.

- Antibiotic resistance: One of its strongest weapons is the ability to survive treatment by common antibiotics. This can happen either naturally (intrinsic resistance) or by gaining new resistance genes from other bacteria.

Diseases Caused by Enterococcus faecalis

E. faecalis is responsible for many types of infections, especially in hospital settings or in people with weakened immune systems. These include:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs): Common in patients with catheters or those who are bedridden for long periods. It causes painful urination, urgency, and cloudy urine.

- Bacteremia and sepsis: If it enters the bloodstream, it can cause widespread infection and inflammation, leading to sepsis—a life-threatening condition.

- Endocarditis: Infection of the inner lining of the heart, especially in people with artificial heart valves or existing heart defects.

- Intra-abdominal and pelvic infections: Often occur after surgery or trauma.

- Wound infections: Can infect surgical wounds or open injuries, especially in hospitals.

- Neonatal sepsis: Newborn babies can sometimes get infected during birth or shortly after.

- Meningitis: Rare but possible, especially after head surgeries or in individuals with weakened immune systems.

Antibiotic Resistance

One of the major concerns with E. faecalis is its ability to resist many types of antibiotics. This makes treating infections difficult and increases the chances of complications.

Intrinsic Resistance

- Aminoglycosides: E. faecalis has a natural, low-level resistance to this class of antibiotics.

- Cephalosporins: It does not respond well to this group of beta-lactam antibiotics.

- Beta-lactams: While penicillin can be effective, the bacteria can often tolerate low doses of beta-lactam antibiotics without being killed.

Acquired Resistance

- Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE): Some strains have picked up special genes like vanA and vanB, making them resistant to vancomycin—a drug often used as a last resort.

- Linezolid and daptomycin resistance: These drugs are used for tough cases, but resistance is now starting to appear, limiting treatment options.

These resistance traits make infections harder to treat and more dangerous, especially in vulnerable patients.

Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of E. faecalis is critical for proper treatment. Laboratories use a mix of traditional and advanced methods:

- Gram staining: A special dye test that shows purple (Gram-positive) round cells in pairs or chains.

- Culture: Grows on nutrient-rich media like blood agar. On bile esculin agar, it turns the medium black, which is a sign of its presence.

- Catalase test: E. faecalis does not produce bubbles when hydrogen peroxide is added, confirming it’s catalase-negative.

- PYR test: A rapid test that turns red if positive. E. faecalis gives a positive result.

- Salt and temperature tolerance: It can survive in salty environments and grow at both cool and warm temperatures.

- Antibiotic susceptibility testing: Labs expose the bacteria to different antibiotics to see which ones work.

- PCR and gene sequencing: Advanced tests that identify resistance genes, especially vanA and vanB.

Treatment

Treating infections caused by E. faecalis depends on how serious the infection is and whether the strain is resistant to antibiotics.

First-Line Antibiotics (for susceptible strains)

- Ampicillin: A common penicillin-type antibiotic that is effective for many E. faecalis infections.

- Penicillin with gentamicin: The combination works better together than either drug alone due to a synergistic effect.

- Vancomycin: A powerful drug used when the strain is not resistant.

For Resistant Strains (e.g., VRE)

- Linezolid: Works well against VRE but should be used carefully to prevent resistance.

- Daptomycin: An injectable antibiotic used in bloodstream and heart infections.

- Tigecycline: Used in complex infections, such as intra-abdominal infections.

- Quinupristin-dalfopristin: Works against E. faecium but not effective for E. faecalis.

Supportive Therapy

- Remove infected devices: Catheters or prosthetics may need to be taken out to fully cure the infection.

- Drainage: Pus or infected fluid may need to be removed surgically.

- Fluid management: Rehydration and correcting electrolyte imbalances can be critical in severe cases.

Prevention and Control

Preventing the spread of E. faecalis, especially in hospitals, is crucial. Some important measures include:

- Hand hygiene: Washing hands with soap or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers can prevent transmission.

- Sterilization of instruments: Surgical and diagnostic tools must be cleaned and sterilized properly.

- Antibiotic stewardship: Using antibiotics responsibly to prevent the development of resistance.

- Isolation procedures: Patients infected with VRE should be isolated to reduce risk of spread.

- Surveillance and monitoring: Regular checks and reporting can help detect outbreaks early and take timely action.

Research and Future Directions

Ongoing research aims to find better ways to prevent and treat E. faecalis infections. Some key areas include:

- Vaccines: Scientists are exploring vaccines to provide immunity against Enterococcus infections.

- New antibiotics: Research is ongoing to develop new drugs that can overcome resistance.

- Biofilm disruption: Targeting biofilms to make bacteria more sensitive to treatment.

- Environmental studies: Understanding how resistance genes spread in the environment and hospitals.

Summary Table

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Gram reaction | Gram-positive cocci |

| Oxygen requirement | Facultative anaerobe |

| Natural habitat | Human and animal gut |

| Infections caused | UTIs, endocarditis, sepsis, wound infections |

| Key virulence factors | Cytolysin, gelatinase, biofilm |

| Common resistance | Vancomycin, aminoglycosides, cephalosporins |

| Diagnosis | Culture, Gram stain, PYR, PCR |

| Treatment | Ampicillin, vancomycin, linezolid |

Conclusion

Enterococcus faecalis acts as both a helpful and harmful microbe. In normal conditions, it contributes to gut health. But when the body’s defense systems are down, it turns into a powerful invader that can cause serious health problems. Its resistance to many antibiotics and its ability to form biofilms make it a top concern in hospitals. By understanding how it behaves, spreads, and responds to treatment, we can better manage its risks. Preventive actions like good hygiene, responsible antibiotic use, and strong infection control policies can help reduce its impact on human health.

Three Key Summary

- Enterococcus faecalis is normally harmless but can cause serious illness when body defenses are weak.

- Its antibiotic resistance, especially to vancomycin, makes infections difficult to treat.

- Strict hygiene and careful antibiotic use are essential for prevention, particularly in hospitals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Enterococcus faecalis dangerous?

Yes, especially for people in hospitals or with weakened immune systems. It can cause life-threatening infections like endocarditis and sepsis.

How is it different from E. coli?

E. coli is a rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacterium, while E. faecalis is a round, Gram-positive one. They also differ in where they usually cause disease and how they resist antibiotics.

Can E. faecalis be cured?

Yes, many infections can be treated successfully with the right antibiotics and supportive care. But resistant strains require more advanced and careful treatment.

Related Articles